May 12, 2015

The sad news about the fading health of blues great B.B. King has got me reflecting on one of those moments in life when you have a clear opportunity to leave stupidity behind. This blogpost could be titled, “How B.B. King got me to stop being a racist.”

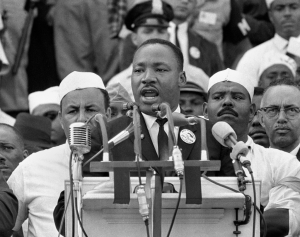

Almost anyone who hears me speak will know I grew up in Stone Mountain, Georgia. Stone Mountain has the distinction of getting a shout out in MLK’s 1963 “I Have a Dream” speech, the greatest speech in American history. “Let freedom from Stone Mountain in Georgia.” It still gives me chills. My town got that distinction from Dr. King because it is the birthplace of the modern Ku Klux Klan. My northern family displayed a gentler version of white southern attitudes. My dad would voice concern about property values if “they” moved into the neighborhood. My mom would lock the car doors if we drove through a black neighborhood. So I grew up in a racist family, in a racist town, in a racist state, in a racist country. It impacted me.

I was raised to be afraid of black people. But none of my experiences matched those lessons. I played YMCA basketball and the black kids were as competitive and nice as the white kids. In high school, I had three quarters in Mr. Krantz’ Folk Guitar class. By the end my best friend in the class was an African-American girl named Sharon Squires. I talked to her about The Beatles and punk rock, she talked to me about dub reggae and the very first hip hop records. Our language of music broke through the barrier of race. It didn’t jive with some of the racist things that came out of my mouth.

In high school, I knew kids whose fathers were in the Klan. I watched the KKK march on more than one Labor Day in my town. In my journalism class, I wrote an editorial titled, “If they can have Black History Month, why can’t we have White History Month?” I needed an escape route from racism. It would be music.

At the tender age of 16, I got a dream job at a record store. It was Turtles Records and Tapes on Memorial Drive. I basically pestered the employees in the Stone Mountain store until they hired me and became the youngest employee in the entire chain. “The Baby Turtle,” as Bono later dubbed me after a U2 show at the Agora. Getting that job was like going to music college. Jimmy, Eric, Nan, Jeff, David and the rest of the gang infused my education with a racial theme.

“Randy, do you like jazz?”

“Yeah, I love Dave Brubeck!” They would put on a John Coltrane record and blow my mind.

“Randy, do you like reggae?”

“Yeah, I love The Police!” They would put on a Peter Tosh record and blow my mind.

“Randy, do you like the blues?”

“Yeah, I love Eric Clapton!” They would put on a Buddy Guy record and blow my mind.

It was clear that my musical upbringing had been squeezed through a white bread filter. I had known it intellectually – Elvis sang Little Richard, The Beatles sang Motown – but I hadn’t experienced it viscerally. Watching David Remy’s face scrunch up when he slapped on Son Seals Live & Burning or Coltrane’s A Love Supreme took me to the core of what the music is about – soul. African-American girls would come into the store, giggle and asked me if I was prejudiced. When I said, “No,” we’d have great talks about Kurtis Blow or Millie James. I was in.

But I still had the fear to contend with. In 1981, the Turtles gang got a batch of primo tickets to see B.B. King with Bobbie Blue Bland and Clarence Carter at the Atlanta Civic Center. If you know the P. Funk song, you know that Atlanta is a “chocolate city.” A blues concert downtown meant this white kid would be a serious minority. What would happen? Would they try to murder me? Or worse, would they blame me for racism? I had black records now! Southern whites loved to blather about “reverse racism,” so I feared the worse.

Our little Caucasian group walked into a sea of black faces and I could feel my heartbeat race. But when we got to our seats, something funny happened. All those black faces smiled at me. A heavy-set woman next to me in a huge purple hat put her arm around me and said, “Sonny, you are going to have a great night. You need to loosen up.” Later, when Clarence Carter played “Patches,” she held my hand and cried. I had the greatest night.

That night I got it. I got the loss that comes from being a racist and I let it go. When B.B. King came out to his anthem, “Everyday I Have the Blues,” I got that, too. Where that comes from. His blues. And his permission to let a white boy from a Klan town experience the release of that pain with him. In that one evening, it all made so much sense to me. The stupid waste of racism. The loss of basic connections between human beings. At that point I decide to do something about it and that became the foundation of my career as a sociologist.

Someone once compared racism to alcoholism. An alcoholic can go for twenty years without a drink, but they still refer to themselves as an alcoholic. I never say I’m not racist. I learned racism at an early age and it exists inside me. I am a racist. But I am also a committed anti-racist, working to undue my white privilege and the systemic institutional racism that supports it. And I owe that position to a bunch of record store employees and a big lady in a purple hat at B.B. King concert. Feminist scholar bell hooks once defined feminism as “a movement to end sexism, sexist exploitation, and oppression.” That night I started moving.

Next: How The Ellen James Society freed me from homophobia.

Randy, what an amazing story and it touched my heart! I too, was raised in the same way, with a (Confederate Civil War veteran) great,great -grandfather who’s Klan outfit was found after his death in a cedar chest. It is strange that all his former slaves followed his son (my great-grandfather) after the war as he gave them jobs and never mistreated them…they loved him. My grandmother was raised with the same racism. Until my high school accepted black students in 1965…was I to know them. Since that time, I have developed an anti-racist attitude and my children, now grown, know no color whatsoever. No matter what the race, there are those who disgrace their heritage. I am proud that I broke that chain with my children. May God continue to bless us with understanding and love for all our brothers and sisters of any race and end the hatred that may still affect those who choose not to want to understand. Thank you for this wonderful sharing! God Bless you!

LikeLike

Really appreciated your blog. Would you be interested in being a guest on our program to discuss this essay and your thoughts on Race.

LikeLike

Definitely! This is my subject. Please feel free to email at blazakr@gmail.com

LikeLike

Thanks for this post. Found it while looking up Turtles, as I grew up in suburbs west of Atlanta and we had a location there. I had similar cognitive dissonance when discovering the music I loved was often birthed of the heartache, struggle, hope, and resilience of African-American people.

LikeLike