May 5, 2016

With the current hostility towards Latinos and “illegal aliens” drummed up by the presumed Republican nominee for president, Donald “Bigly” Trump, I thought I’d hand over my blog to my wife, Andrea. She is one of the people the Trump thugs will be looking for, so her voice is much more powerful than mine on this topic.

She’s also a much better writer than I am. When I first read this, I wept for what she’d lost to be here in the “land of the free.” This piece might remind you of the great Mexican writer, Octavio Paz. Or it might remind you that we are all continuing journeys that our families began for us. In honor of the hard working people who won’t be drinking margaritas today or having sombrero contests, please spend some time with mi familia.

A Conversation with the Serpent

This creature inhabits two worlds. Split in uno, dos. This same creature never leaves the borders she was made to cross. Those unnatural lines. They are sticky, tangled, and wherever she goes, they wrap around her ankles and pull down as the creature walks, as if to remind her she is not home. The serpent woman looks down at them, smiles, then keeps moving.

“Entre mas bien te portes, mas bien te va a ir” you said to me once. Yes, you told me once and left me puzzled. You, Anastasia, the boss lady of the Rosas clan. Eighty some years old, with hoses for veins. I’m not sure how you came to be, how you came into this world. You seem too old for anything to have created or birthed you. You look and smell like sweet tree bark as if you had been standing there, in that same spot, taking root for years and years just watching Mexico’s story unfold from the time of the pyramids to now. Tienes una calma admirable. You have that calmness about you, the kind of calm serene spirit only the air between strong growing trees have. You were never taught to make sense of letters, but have always had plenty of wisdom to share about how a life should be lived. You represent our land, Mexico, in all it’s wholeness, with all it’s jungles, trees, garbage, tierra, oppression, cactus, esqueletos, all of it. Your words are always so sure of themselves, they stand over us and give us a dirty look when they come out of your mouth. “The better you behave, the better life will be to you” you said. With iPhone in hand, I recorded your voice without you noticing. It might be the last time I would get to hear it since I moved North, to the United States of America. Your voice. A voice that reminded me of the one place I belonged to and wanted to hold on to, but also a voice that yanked on the back of my neck hairs and reminded me that I wasn’t there anymore. But it wasn’t until I crossed over to the other side that your words made sense. Only there, in between worlds, on that shaky bridge, did I find the meaning to your words. I found what you really meant to say. Split into uno, dos.

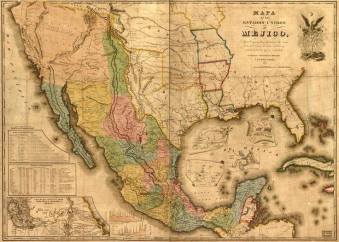

When our people move North and cross the waters of the Rio Bravo to the other side, we get split into two. It’s funny how even the river that divides this land and that land has two names: they call it The Rio Grande, the “big river.” We call it El Rio Bravo, the “angry river.” Different names, different experiences. Split into two. Everything about me seems to be split in two. You would never understand because you are whole. You have all your parts and know them well, because they have been a part of you always. You’ve never had to add or subtract anything from yourself. Everything is where you left it, just the way you know. But me, my everything splits into dos ever since I left our place. I have two heads, two tongues, two brains, two, two, two. Two mouths, two homes, dos modos de ser, two. And just like the Mexican female goddess was split into two by Spanish religion, split into the virgin and the whore, Tonantsi and Coatlalopeuh, I too, along with all the women in your family have been split. Octavio Paz would say we, the women of your country, only become more damaged when we cross over, because according to him we are born damaged. He says women are born with a wound that never heals. A raja or opening that bleeds out every month to remind us we are weak, and sinful. He repeats that “a woman is a domesticated wild animal, lecherous and sinful from birth, who must be subdued with a stick and guided by the reins of religion.” He would say that when we cross over and abandon our homes the wound tears and only opens up more and we bleed out.

But I know you, and I can see you start to laugh, and I know how you raised us, and I can hear you tell Paz that he can shove his book up his ass. Up his on raja. You never needed nada de nadie, nothing from no one and would be proud to say you bleed and are still strong. I can hear you say that to me and tell me that you are both the whore, and the virgin. You were both La Llorona and La Malinche. The wailing woman, crying your songs for her lost children at the river by the border, and the one who Cortez slept with because he wanted your power. You are both Tonantsi and Coatlalopeuh, and are not gonna apologize for any of it.

In a way, I have always been jealous of your life, grandma. A life with a poor but constant home. A life that to American standards would seem miserable. But you live happy because their standards don’t exist to you because you who have been untouched by American culture and expectation. You own and know yourself so well, unlike us on the other side who have two faces, because having one would not be enough. We keep a third face in our closet because it’s too sad for even us to look at. So you see us, on this side of the line, and we walk cradling our dried up roots in our arms, with our two sad brown faces swinging as we go. You are whole in the way that I cannot be. You are the constant force, the motherland. Just looking at you, a serpent woman, could scare you in the sweetest way. You know when you do it don’t you abue? You know when you scare us because after you notice, you smile and your face gets all wrinkled with satisfaction. The same half fear is what I feel when I think of returning home, to what our country has become. The kind of fear you want to feel because it feels good. Home scares me, but it’s impossible not to long to go back, not to go back crawling into familiar arms.

You and our country are full of life, but also full of holy death. Death does not scare us. Magic doesn’t make us laugh. You taught us to live with it, to not fear it. You and our ancestors have built altars to venerate lady death, la flaca, la huesuda. You light the dead candles so they can find their way back home once a year, and set out a feast of bread and tequila for them to enjoy while we sleep and they dance around us. You don’t let us go out into the streets without “La benediction” for fear of the spirits, but mostly out of respect for the evil in all of us. You cover the mirrors in the homes when someone in the family dies, you say that if you don’t the deceased will take us with them to that other place, and you say it’s not our time. You believe in the life in us, but also teach us that we should not be scared of death. All your beliefs intact because you’ve never crossed to the North. It’s another world, Grandma. In the words of Gloria Anzaldua, your beliefs would be classified as “fiction, make-believe, wish-fulfillment.” they say that “Indians have primitive and therefore deficient minds.” And that label, is what our people deal with on the other side. We are classified as having deficient minds because we believe in gods and goddesses that don’t line up with theirs. So we stand here and are scared to hold onto our brown Gods, and the Gods sense we are scared. They know it and frown and slowly step back from us, leaving us here, on the other side with nothing to believe in. All that is left is the holes in our bodies from when we were whole, but now are hollow. The further our people get from our brown Gods, the closer they get to the United States.

You grew up with the land and the land grew with you and around you; framing the beautiful lines on your face. Grandma, unlike in your old Mexico where the trees are welcomed into homes through the windows and doors and wrap around the houses in a protective embrace, or where the dust and soil are like part of the family, or where the fireflies light the red sky, the scenery in the United States is not welcoming. It doesn’t embrace you. It doesn’t grow with you. It grows, expands, decays, grows again, never once acknowledging your presence. A neighborhood once full of life gets bought out to make room for bigger and better concrete. All while the people with our skin color get pushed out further and further into the decay. And from that decay, they rebuild and dwell. The United States hosts so many of our peoples bodies, but it never really welcomes them. There is always that awkward feeling floating around the air that one gets when a guest has overstayed its welcome and both parties smile nervously awaiting for a departure. You know that nervous feeling Grandma, I saw you make that face when your comadre wouldn’t leave last Saturday night after you had coffee with her and your tired obsidian eyes just danced around her as if you were trying to cha-cha her right out of your house. I know you feel for me, and feel a loss. Because even though your roots are firm and stable, you see that ours aren’t and you can’t do anything but watch us leave and return tired. Our existence here is uncertain. Our limbs decaying. You notice how damaged our roots are from the transplant and dried up from not having a stable place to grow into and hold on to. The soil is not the same. Our people can’t grow on concrete.

It’s too bad you brought us up with so much pride, I think to myself sometimes. It’s all your fault Anastacia. You, the warrior goddess who raised and fed all those children on corn you grew on your back. You, who reminded yours that you brought them into the world and could take them out of it, if you wished to. Yo the traje a este mundo, y si quiero te puedo sacar, you would say. You and your proud serpent spirit, the shadow beast. You never needed nada de nadie, and you wished the same for us. You infected all the women in your family with that same spirit, the same pride. The same kind of pride I hate when I see it coming from the whites who say all the illegal aliens are taking over their country. But I just look at my skin and the constellations my moles make on my arms, and the patterns they make remind me of yours and I laugh. I laugh because I don’t blame them, not always. I imagine them moving South and bringing their dull religion and customs with them and I cringe. I understand they are only trying to protect the little identity they have. Their red, white and blue colored pride. But yes abue, that same pride has taken over me, it both empowers me and tries to trip me up, to hurt me as I go. The pride is like the ancient serpent goddess: it will let you grab a hold of her but you never know her mood. She might be at peace that day and just dance in your hands, or she can grab you using her fangs and coil herself tightly around your arm. But, because I can’t hold on to you or our country, I risk it and I grab a hold on to that pride shaped like a snake.

I blame all this pride on you. I have a hard time deciding if it’s useful or not. Like the old Aztecs, the one’s before the warfare tactics took over and the female spirit was split into two and before the Spanish rapists tried to erase our spirit, I, like the old Aztecs grew up with you, with a matriarch, as the goddess. Even if you, the aging goddess never misses Sunday mass and makes us, your grandchildren stand and kneel and stand again and praise the bleeding male God on the cross. A God that was pushed on you and us, but one you took in because you saw that he too was an orphan. I wonder if you know we praise you? And stand and kneel only for you. You are our God, our Tonantsi. Blessed are you amongst grandmas. Bendita seas tu. You who can make water turn into tequila, and provide it for our whole family who faithfully drinks for their sins every Sunday.

So you ask me what changes when you go North and you ask me why I return to you so pale? Grandma, you don’t know this, but the further North you go into the US, once you cross, the paler the air gets. Air so pale and dry it strips your skin of colors. So please, stop teasing me about being so pale, it’s not my fault. You can rub all the beets in the world on my face and I still wouldn’t get the color I once had, the color I had before I left. I still qualify as a person of color to the whites, so that’s something, right? I agree with you, the air, the rain and clouds in the U.S. are cabrones because they keep our people so colorless, so pale. We can’t even wear our rightful brown skin. The browns and reds and burnt yellows we inherited from our aunts and uncles, the Aztecs and Los Mayas. Instead we walk around with just enough of a lazy brown to make us stand out from their whiteness. Enough to make us different. Enough to make us “aliens.” Brown aliens. So our color get’s washed away, slowly being taken away by the foreign clouds and the American rain. Our color washed away, but never our stupid pride, Grandma.

You ask me why I come back so thirsty? You don’t know, but there are less real cantinas, or what you call them “Mexican water holes.” Less gossip, and less mercados– yeah the ones with the piñatas on the ceiling, and the pig heads hanging from hooks, and the smell of the spices and candied air… we don’t have those. The mercados or tiendas that do exist are here for the amusement of the whites, so they can feel all warm and fuzzy and cultural. Whites like to buy all our colors, even if they are overpriced. I once went into a tienda and tried to have a conversation with the person at the counter taking my money and all I got was my change back and a “I don’t speak your language, I’m not Mexican.” back. I don’t like that they accuse our people of not belonging, yet take our colors to make up for the lack of theirs. They take us and leave us as they please. They like some parts of us, but not the whole. The whole is too much to handle. Too much of a bother to deal with. Too much to understand. We are not as simple as they want us to be.

You ask me why I come back so tongue-tied? Why do I come back hablando chistosito? My r’s weak from the long trip. English, which was once unnatural to me tries to take over my mouth and you notice it and frown. My tongue is too, split into two. And with my serpent tongue I speak here and there. Each end of the tip of the tongue dancing to a different rhythm. Our people are so confused when it comes to language. We can’t speak Spanish, but some of us don’t know English, so we mix them together. Un revoltijo de lenguas, but that isn’t acceptable. The mixing of languages isn’t acceptable, it’s illegitimate, like us. Our people have created a border language, a language that lives on the bridge where we too live. “Deslenguadas. Somos los del español deficiente. We are your linguistic nightmare, your linguistic aberration, your linguistic mestisaje, the subject of your burla. Because we speak with tongues of fire we are culturally crucified. Racially, culturally and linguistically somos huerfanos– we speak an orphan tongue.” says Anzaldua. I hear stories of parents who prohibit their kids from learning their mother language for fear that if they speak something other than English they will be seen as less. Don’t they know they are making them into “less?” I am thankful of my tongue split into two when I hear stories like this, because I’d rather have the tongue of a serpent, split into two at the end, than to not know las palabras que salen de tu boca. In the wise words of Ray Gwyn Smith, “who is to say that robbing a people of its language is less violent than war?” And war is what those language borders create in our Mexican heads, but Grandma you wouldn’t understand. Your tongue is agile and your r’s are strong.

You ask me why I run wild into the sugar cane fields in the back of your house, in and out and in and out. I run wild when I come back to stretch out the stiffness of life on the bridge. because our people are tired of hiding. We are so used to hiding up north. We are so tired of burrowing our brown faces deeper and deeper into the ground for the fear of being seen, being caught. So tired from giving in to the addictions of hiding out behind our masks. Our people get home from work and in their isolation sit and eat their loneliness. Only they know how lonely it is to be here, not surrounded by people who look like you, who sound like you. That is what life is like on the bridge, and it get’s tiring. So when we are back on the other side of the bridge: our side, we rejoice and drink, we take off our masks, sun our faces and shoot guns into the sky like fools who wish to reclaim what they left behind. To shoot it down from the heavens hoping we have the right aim and that thing we’ve been stripped from when we left falls right on our heads.

You too, have asked me why our people come back so slouched? Todos jorobados. With green dollars in their hands, but slouched. I think the expectation is for our people to check their pride at the border, you see, and some do. Some forget who they were before they walked with the masks over their face, their real face. They don’t light candles for their deceased, they don’t remember how not to fear, they are scared to look at their faces, they are scared of death. Not me. I managed to sneak that pride in just like the bottles of Mezcal, the kind with the little worm I always manage to sneak in when I fly back now that I have my papers. Now that I was given a piece of paper than says my crossing over doesn’t have to be the cause of my death. A green plastic card with my brown face on it that says that I’m one of the lucky ones that can go out into the streets without the fear of being kicked back. I managed to sneak in that dark pride you gave me because its color matched the black and blue night over our heads the night we crossed the Arizona desert. That night when I and the other sixty something brown faces full of color crossed the dusty Arizona desert leaving tracks on the sand with our bellies as we dragged them through. The blue night we had to claw ourselves into the ground to hide from the border patrol in order to cross over to a land that once belonged to our people. We didn’t fear because in some way, we had already been there. The desert recognized our faces and said hello and helped us on the way.

The desert trusted us and said “I missed you” and “come back.” A desert that hid us behind her black arms so that we could make the journey back to our old land safely. We knew the way and the way knew us.

So the pride was snuck in, but something else got left behind. Either something gets left behind or you pick something up as you cross into this country. Whatever it is, you never get it back. Whatever it is it’s heavy and makes the Mexican men walk all slouched, not like the men who walk like roosters on Sundays in your little towns plaza. I see the heaviness of that thing weigh down their bottom eyelids. Sometimes that thing is so heavy that their whole head tilts towards the ground. Sometimes it splits them in half and you see only half of their body moving as they go, just when you think Mexican men can’t be any more damaged. Half of our women and half of our men out here in these American streets. Fragmented by their struggles, stripped of their beliefs, little decayed beings.

“But I’ve behaved badly, and life has been pretty good to me” was what you said to me once, after that other thing you said to me. Then it all made sense. You, with your twisted tongue, the cactus goddess, said with your eyes, a message in code that I don’t even think you understood. You could not have understood what it would mean to be because you are whole. You said to me in code, and I understood. You knew you hadn’t conformed, no te portaste bien. You had owned both the light and the dark in you, the virgin and the whore. You didn’t let anyone take your wholeness away and that is what you wanted for us. That was the only way to be for you. You weren’t speaking to me as the virgin, or the whore. You owned your everything. And that to you was the only way to behave “well.” You let our ancient goddesses speak through your eyes and told me to hold on to that thing they passed down to you, and you to me. To our people. I finally understood your words on the bridge. You tugged down on my ankles and I smiled at you.

Helluva post. Beautiful. Thank you.

LikeLike

how very lovely. i never thought about what you left behind. also thought you were lucky to be in our country. i didn’t consider you left a culture that you loved and understood, for a strange land. sometimes that new land did not welcome you or treat you kindly, thinking we are better than you are. for that i apologize. i feel the same unwelcome when i have gone to your country. the language and food and customs are as strange to me, as ours must have seemed to you. how sad, that most of the time, we can’t just be human, not one race or another. we would learn and gain so much. i can only say welcome and will now have better understanding of what i see when i interact with your culture.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Reblogged this on Poem Blogger and commented:

MAY 5, 2016 ~ RANDY BLAZAK

LikeLike

Though 3 weeks late, I have thoughts to what Andrea Barrios wrote though covers only part where she wrote of los conquistadores, Aztecs & Mayas. Yes, los conquistadores did what was in Spain’s interests. But though I think Andrea Barrios knows this, for her to imply Aztecs were ‘noble savages’ living in peace with other Indians isn’t honest. Yes, los conquistadores sometimes raped Indian women but Andrea Barrios omits that Aztecs also sometimes committed rapes in that Aztecs would kidnap other Indian women & girls to take as wives. Aztecs also had human sacrifices. Pre-Columbian Aztecs and Incas conquered other tribes before los conquistadores Hernan Cortez and Francisco Pizarro conquered them. This gets to los conquistadores from Spain (Portugal for Brazil).

Hernan Cortez got alot of help from Indian allies during conquest of Mexico, which took him 2 years to do. Los conquistadores were able to conquer Mexico because among other reasons they got help from Indian allies who were not happy being under the Aztecs. Los conquistadores would tell Aztecs, Incas & other tribes was that the Indians had land, metals (iron, gold, silver, copper & bronze) which they wanted, that to give it to them, or they’d fight a war to take it. They did this for Spain’s interests, which ended with 300 years of Spanish and Portuguese colonisation (Brazil). Colonization of Iberoamerica by Spain and Portugal in the 1500s would be imposing culture, including religion (Christianity) on Native Americans. I am against this as I believe in democracy and free will. I oppose el sistema de las castas which existed in Iberoamerica. But I also would not have wanted to live in Mexico during time of Aztec sacrifices & Andrea Barrios gives Noble Savage Myth here.

LikeLike

^^With my post above, point is not to agree with los conquistadores because los conquistadores did what was for Spain & Portugal’s benefit @ American Indians expense. Point is that it’s dishonest to imply Aztecs were peaceful as Paintress Andrea Barrio implies. No, Native American tribal wars did not go into other continents while the conquest of Native Americans by Europeans did. But the idea is the same. if Aztecs had the advanced technology, the Aztecs would have been conquering other places in world as the Aztecs conquered other tribes before the Aztecs were conquered. When it comes to thinking, people are the same. American Indians must be treated fairly. Aztecs must be treated with fairness. In fact, all ethnic groups must be treated with fairness. But to make Native Americans to be Noble Savages who lived in peace is dishonest.

LikeLike

This will be a long post. Other things-I lived in Spain from 1981 to 1984 (I speak Spanish) & have been to Spain twice in my adulthood 2012 (Madrid, el escorial, Segovia, Avila & Salamanca along with visiting Fatima Portugal & Lisboa Portugal) & in May 2014 (Madrid, el escorial, Toledo, Cordoba & Sevilla). Spaniards & Portuguese are nice. Have also visited Costa Rica in Sept. 2013.

With Mexico, my guess is that Paintress Andrea Barrio is Mestiza-Spanish & Amerindian mixed. If she is Mestiza, there is no need to put down her Spanish ancestry. Yes, Mexico & other Iberoamerican nations were Spanish & Portuguese (Brazil) colonies but they have been independent since 1800s. When it comes to thinking, Spaniards, Portuguese & American Indians are the same, only that Spaniards & Portuguese having better weapons were able to colonize. & again, in the case of Incas & Aztecs (Mexico), los conquistadores took away American Indian conquests. Paintress Andrea Barrio also knows that US tourists travel most to Mexico & it’s American companies who do work in Mexico. Gringos do help Mexico’s economy.

American Indians must be treated fairly, fairly but also treat Europeans fairly. After the 2016 Ecuador earthquake, Spain was 1 of nations which sent help to Ecuador, it’s former colony. In my next 2 posts after this 1, I’ll discuss Venezuela’s Nicolas Maduro. Though Paintress Andrea Barrio knows this, with American Indians or who are sometimes called Native Americans, American Indians ancestry goes back to Asia. Sioux & Orientals would be distant cousins thousands of years earlier. Wouldn’t be surprised if with some of the Indian tribes in Mesoamerica, if their ancestry goes back to India. They have found mummied remains of Whites in Peru & Mexico, though this # is small, so there were a few Whites living there.

I have read comments by Whites raising the fact that they treat Blacks, American Indians & other groups fairly & that it’s wrong to condemn them for past wrongs which happened long ago, such as slavery. I believe it’s wrong to condemn people for past wrongs & what matters is that they are fair. But there are Blacks, American Indians who condemn Whites no matter how fair a White person is. This condemning is wrong. If a White person treats a Black, American Indian, etc. fairly, then don’t make an issue. All ethnic groups must be treated fairly, which also means that American Indians must treat Whites fairly. I support democracy and = rights for all ethnic groups.People are the same everywhere-Whites, Blacks, American Indians, etc.

Anyhow, if it is about seeing American Indians have same rights as all others, then I support that. American Indians must have = rights when it comes to jobs, housing & = punishment for crime based on facts & circumstances of each case. I am against discrimination. But it must not be an us against them thinking & let’s not have the Noble Savage theory because hypothetically, American Indians would have done the same thing if they had the capability or capacity to do it as people are the same everywhere. If American Indian tribes (esp. tribes like the Sioux, Comanches, Apaches, Aztecs, etc.) had better weapons & capabilities, they would have been conquering other places in the world & imposing their laws on others. What I’ve found with American Indians is that many times when they talk of ‘stolen land’ what they imply is ‘you did what I wanted to do.’

LikeLike

BRAVO, well said!

LikeLike

With this post & next 1, though it’s indirectly related to Paintress Andrea Barrio’s article in that it’s about Venezuela (a nation which like Mexico used to be a Spanish colony), it is indirectly relevant as it’s about Spaniards. Venezuelan dictator Nicolas Maduro Moros critiques Spain’s Leader Mariano Rajoy Brey because Spain supports Venezuela’s opposition by saying 1. Spain should only care about Spain’s problems & not meddle in Venezuela’s affairs. 2. Accuses Spain’s PM of colonialism, racism, etc. With #1 , nothing wrong with that but Nicolas Maduro Moros sponsored Spain’s party Podemos to push policies favorable to him so Nicolas Maduro Moros talks with forked tongue. With #2 , while I don’t always agree with Mr. Mariano Rajoy Brey, bringing up past colonization is wrong. Nicolas Maduro Moros is a dictator, almost as bad as his ally Cuba’s Castro. Spaniards must not be censored for speaking against Venezuela’s Nicolas Maduro Moros because Venezuela was once a Spanish colony.

LikeLike

This contin. & finishes my last post. Spain’s Pres. Mariano Rajoy Brey is wrong to support bullfighting as there are faster ways to kill for food such as rifles. Most Spaniards under 30 years old are against bullfighting. Pres. Mariano Rajoy Brey is right to be against Cataluna trying to unilaterally be a separate nation by referedums and Pres. Mariano Rajoy Brey is right to be against Venezuela’s dictator Nicolas Maduro Brey. It’s not racist to bring up fact that Nicolas Maduro Moros morally supports FARC guerrillas and drug traffickers. Venezuela’s Nicolas Maduro Moros is corrupt.

LikeLike