February 5, 2018

I’ve got eighteen interviews in the bag for my Recovering Asshole podcast. Each of them has been a step on the path of me understanding my vast privileges. I’ve learned about white fragility and what it’s like to live in a large woman’s body. I’ve gained insight from transgendered, immigrant, and even left-handed perspectives. Perhaps the most revealing interview was the most recent one (#18) about disabilities and ableism. My desire to have this conversation was rooted in my fear about not knowing how to talk about and to people with physical and mental disabilities. My shame was the realization that, in my life, I had probably done more harm than good.

As a sociologist of extremism, I’ve lectured about the history of eugenics in Hitler’s Third Reich. The first act of the “Final Solution” was the “Law for the Prevention of Progeny with Hereditary Diseases.” All people with an “inherited disease” (which included everything from physical “deformities” to alcoholism) were ordered to be sterilized in an effort to perfect Germany’s Aryan “master race.” In 1939, Hitler began Operation T4 that killed over 70,000 disabled Germans and Austrians in one year, utilizing poison gas as a warm-up for the mass extermination of Jews and others in concentration camps. Of course, the United States had it’s own eugenics programs that included the forced sterilization of “unwanted” populations.

But, as usual, we are appropriately horrified by the extreme manifestations of such bigotries but are unable to identify the same tendencies and leanings in ourselves. “What could I possibly have in common with a Nazi?” we ask as we skip over a news story about the brutal genocide of the Rohingya occurring in 2018.

My podcast interview was with Grant Miller, who is a Portland disability activist who works with a great arts program called PHAME, and is working with Portland Art Museum on disability access issues. I really wanted to dive into a conversation about how we even talk about people with disabilities. Does Grant “suffer” from a disability? Is he just “differently abled”? As I progressive as I think I am, I realized I didn’t even know what kind of language to use. I always tell folks, when in doubt about subjects like this, just ask the people themselves.

I prefaced this conversation with caveat that my path towards empathy really began in 2002 when I had a brain hemorrhage and a subsequent stroke. I was in the hospital for almost a month and had to relearn how to walk. Suddenly, I was the guy holding up traffic as I slowly crossed the street with a cane. I reflected on all the times I had gotten angry because of the speedy norm of modern life. Hurry up!

You can listen to the interview yourself (or the read the transcription, which I hadn’t even considered until Grant pointed it out). It’s 60 minutes of me stepping in it. They are not “hearing impaired” people, they’re deaf. People aren’t confined to wheelchairs, they are wheelchair users. (Many people are, in fact, liberated by wheelchairs.) Even the way we use metaphors disregards the experience of the disabled. You can’t “walk in someone’s shoes” if they can’t walk themselves. You can’t have “you eyes opened” to an issue if you are blind. All this reflects our internalized ableism.

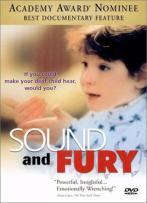

What we have in common with Hitler is the persistent belief that there is an absolute definition of what is “normal.” That if your hands, or legs, or brain don’t work the exact same way mine do, you are some sort of abhorrent deformity that needs to be fixed, no matter how invasive or traumatizing the process might be. My awareness of this was raised by a deaf student of mine at Portland State who shared a brilliant 2000 documentary about cochlear implants called Sound and Fury. Perhaps well-meaning doctors, with new technology on their side, have begun to “cure” deaf people with these fancy Star Trek-looking brain implants. What the documentary points out is that there is a thriving Deaf community that doesn’t need to be “fixed.” If we just bothered to learn their language (American Sign Language), we could’ve just asked them.

And that’s the theme of the ableism – that “they” (people with various disabilities) should be more like “us” (people without disabilities) to be more “normal.” My city, Portland, had laws in the 1880s that are now known as Ugly Laws. They made it virtually illegal to be in public if you were “crippled” or “deformed.” You could be arrested and fined. There’s an amazing 2007 movie called The Music Within that’s about the birth of the disability rights movement, and there’s a scene in that movie (filmed in Portland) where a man with a severe case of cerebral palsy is trying to dine in a Portland restaurant in 1974 and is arrested under one of these Ugly Laws. That act was the genesis of the movement that gave us the Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990. It’s a powerful scene. How dare this man be disabled in public? He was making “normal” people feel uncomfortable!

Why were they uncomfortable? Could it possibly be their ableist privilege that was poking them in their chest? But then maybe before getting all high and mighty about a scene in the movie I should look in the mirror.

I was in high school in Stone Mountain, Georgia in the late 1970s and early 1980s. It was the period before the ADA began making institutions more accessible but after the period when the best career trajectory for the disabled was in a circus sideshow. (Although, I am old enough to remember the Florida sideshow attraction known as Alligator Boy.) It was a time when kids with disabilities were beginning to be “streamlined” into the general public school population and, like those white students at Little Rock Central High School in 1957, we weren’t exactly welcoming.

It sickens me to say this, but not only did we give those kids a wide birth, like their disabilities were contagious, we shared “funny” nicknames for them behind their backs. (I won’t repeat any here. Just know I am in tears as I write this.) I know teenagers can be cruel, but I have to think the obstacles these fellow Redan Raiders faced just to make it to the end of sixth period had to have been greater than anything I could imagine. And no doubt they suffered from their social isolation. I missed out not only their potential friendship, but being a better person by witnessing their courage in just showing up. I participated in their marginalization, no doubt diminishing their high school experience, but I also hurt myself in the process. I’m thinking of digging out my yearbook and trying to track them down to see if it’s not too late.

All forms of bigotry are based on dehumanizing people who don’t fit into the dominant group’s definition of “normal.” Blacks, homosexuals, Muslims, and even the left-handed have, at times, been defined as less-than or even sub-human. Slave traders believed Africans had no souls. (That was B.A. – Before Aretha.) People from Latin America without proper immigration papers are “illegals” or “aliens,” not human beings. There is no clearer example of how this tendency works than how we have demonized people with disabilities as “abnormal.” We might not be overtly racist in polite company anymore, but saying, “That’s so retarded” barely gets a reaction. Add racism, sexism, anti-Semitism, Islamophobia, homophobia to the recipients of those bigotries to someone who is also disabled and you get a recipe for some old fashioned hate.

Our current way of thinking about disabilities, whether congenital or acquired, is rooted in the medical model. Disabled people have a problem and therefore are a problem, but one that can be, at least partially, fixed. And if not fixed, then we can find a place for them, either out of sight or working (for reduced wages) at Goodwill. The disability community is pushing for a more social model that places the root of the problem, not on the person, but how society is organized to marginalize that person. The barriers can be physical. (Are doors wide enough to accommodate people who use wheelchairs?) The barriers can also be our attitudes, including falling into the classic “us vs. them” dichotomy. There is only us.

According to the 2010 census, nearly one in five Americans experiences some form of disability, and yet so many of these physical and attitudinal barriers remain. I’d like to highlight that that means four in five Americans might be missing out on the benefit of the full participation of the the other fifth because of our fear or ignorance or indifference or belief that we are somehow more “normal” than the disabled. Thanks to my conversation with Grant, I understand (I didn’t say “see”) this issue more deeply and am ready to be the advocate I should have been in high school. I see you. All of you.