I’m occasionally posting some chapters from my “rock memoir,” Jukebox Hero. April 29th is always a day I think of this little story.

Jukebox Hero 1: Queens of Noise – The Runaways

Jukebox Hero 2: I Will Follow – U2 (Part 1)

Jukebox Hero 3: Right Here, Right Now, Watching the World Wake Up From History

Jukebox Hero 4: Feed the World – U2 (Part 2)

April 29, 1985 is a date that will live in infamy, and not because it was the day the president declared May “National Elders Month.” It was the day I finally became a rock star. It was also the last day of classes of my wild college career. I was about to graduate from Emory with a double major in Sociology and Political Science. It was also No Business As Usual Day, a day of national protest against Ronald Reagan, the military industrial complex, and the race toward nuclear annihilation. I had organized a major teach-in on campus that afternoon that was the culmination of my college activism. And perhaps, most importantly U2 was playing at the Omni Coliseum. I had used my connections to get tickets right up front and couldn’t wait.

By 1985, U2 was on their way to being the biggest band on the planet and people knew I had an inside line. “Introduce me to The Edge!” The best I could do was suggest that if you wanted to meet the band in Atlanta, just hang out at Martin Luther King, Jr.’s tomb on Auburn Avenue. They would surely be there to pay their respects to the man who was all over their new album. He was born and rested in Atlanta. I’d have been there if I hadn’t had classes and the big rally. That advice paid off as Bono, Larry, Adam, and Edge stopped by and were mobbed by white kids.

At the show, the crowd was beyond excited. Those who hadn’t seen the band before knew, from videos like U2 Live at Red Rocks, that U2 shows were more like religious events, with Bono risking his neck to get close to the fans. At most concerts, after 20 minutes, you’ve pretty much got the experience and are ready for the next stimuli. At a U2 show, you just didn’t want it to end. The Red Rockers did a fair job opening the show, but when the Irish lads opened with a rare B-side, “11 O’Clock Tick Tock,” the place was transformed.

As usual, I had girl drama at the time. I was sort of between girlfriends. I had been dating Mary, who was a manager of the Record Bar at Lennox Square. I had just started dating Starla, who was an Emory freshman and working model. That spring I was in love with a Bangle (another chapter), so of course I went to the show with my friend Paige, who was a friend from Athens and manager of The Kilkenny Cats. Mary, and Starla both managed to find me on the floor of the arena, which added to the vibe that I was at the center of something big.

Throughout the show, I pressed against the stage and tried to catch Bono’s eye. He finally saw me and in the middle of a song, shouted, “Randy!” Paige smiled and the people around me looked at me curiously. When he came over to me, I handed him a No Business As Usual flyer hoping he would announce it to the 18,000 people at the Omni. He looked at the piece of paper with confusion and just went into the next song. Bono mentioned spending time with MLK that afternoon and then they finished the concert with “Pride.” But no one was going anywhere.

The crowd was singing, “How long to sing this song,” from the U2 song “40” when the four came back on stage. Bono talked about how anyone can be a rock star and then asked if anyone in the audience could play guitar. He pulled a tall, curly-haired guy out of the front row who was more than happy to be on stage with U2. Bono carefully removed his biker gloves and handed him an acoustic guitar. Turns out after all that, the dude couldn’t play the guitar at all. Bono looked down to me in a bit of a panic and asked, “Randy, can you do this?” I looked at Paige and then at Mary, who beamed a big smile, and I gave my hand to the rock star so he could pull me on to the stage. I was magically lifted through the barrier that divided fan and band.

Bono, placed the guitar on my shoulders and gave me the chords for Bob Dylan’s “Knockin’ on Heaven’s Door” – G-D-C, G-D-Am. I knew the chords from my Folk Guitar class at Redan High, and had learned to play a few Dylan and Neil Young songs since then. I could do this. Of course, I was on stage with my favorite band, in my hometown, in front of 18,000 screaming fans, including Starla, who I was really hoping to impress. In the one picture that survives from that night, I look like I belong in the band. I did. I was in U2!

We rocked out on “Knockin’ On Heaven’s Door.” I couldn’t really see the crowd because of the lights, or hear them, because I was trying to hear myself play the right chords through the monitors. I just remember looking at the carpet on the stage and thinking, “OK, this is just like jamming in a living room in Dublin.” It felt so right, like I belonged there. All those years of playing air guitar in my room to Who records, imagining thousands of screaming rock fans. There was no Eddie Van Halen solo but I went for the power chord, especially on the E minor. I focused on getting it right but I knew everyone there imagined it was them on stage. I was there to represent the dream of every rock fan. I think that was Bono’s idea of the whole bit.

At the peak of the song, Bono, Larry, Adam, and The Edge walked off the stage and left me to play by myself. I could now hear the crowd cheer. I did my best Gene Simmons imitation and wagged my tongue at them. The band returned and ended the song in a big crash. I’m sure it was better than I could’ve imagined, but I barely remember it. It was a truly out of body experience.

I climbed back down to my seat, acting like the whole thing was planned. U2 launched into “Gloria” and I got a thousand hugs, including from Starla. After the show, I saw the band’s tour manager who said that Bono had been trying to call me. In the days before cell phones and cheap answering machines, I relied on my dorm mates to answer the phone in my room. Turns out Bono had called my room and somebody on the hall hung up on him, thinking it was a crank call. Mary let me know she had backstage passes and if I would say goodnight to Paige, I could meet up with the band.

I ditched poor Paige and Mary and I joined the “special” people who had after-show passes. Lots of record business types and maybe a few contest winners. I hit the deli tray and scarffed cheeses while Mary got the band to sign her Boy poster. I was a friend not a hanger on. The Edge came up and gave me a pat on the back, complimenting my crappy guitar playing and then Bono approached me, with a handler keeping the over zealous fans at arms’ length. He seemed really wiped out by the show but we laughed about how funny it was that I was in the right place at the right time to help out. He suggested I come by the hotel for breakfast the next day and then he disappeared into the catacombs of The Omni.

The next day I rode my scooter down to the Ritz-Carlton on Peachtree for my breakfast date with Bono. They were heading off to the next show in Jacksonville, Florida so we didn’t have too much time to socialize. The Maitre ‘D didn’t want to seat us because of our attire. Bono was in ratty jeans and a gypsy shirt and I was wearing a blue tie-dyed jump suit I had bought on King’s Road in London. Fortunately, a young waitress whispered in his ear. Probably something about him being the biggest rock star around and me being a guy in a tie-dyed jump suit. We caught up and talked about our demo project and my love life. Why on earth I spilled my guts to him about my failed romance with a Bangle, I’ll never know. But he listened intently. Then we talked about the activism on college campuses around issues like the contras in Nicaragua and apartheid in South Africa. I explained to him the whole No Business As Usual Day thing and he said he’d wish he’d announced it at the concert. Bono also mentioned he would be doing a record with Steven Van Zandt protesting apartheid, which ended up being the brilliant “Sun City” record.

I noticed a change in this version of Bono who had suddenly become a global icon. He paused before he said anything, like the wanted to make sure he said the right thing. Maybe he thought people were going to start quoting everything that came out of his mouth. He was certainly more thoughtful, but I missed the more playful guy from The Summit in Howth.

I have to admit that, things for me seemed to change a lot after that show. I couldn’t go a day without someone shouting out, “Hey, aren’t you that dude that played with U2?” Half my friends were convinced the whole thing was staged, including the bit with the guy who couldn’t play guitar. I tried to tell them that they did that bit at every show on the tour. I gave up on my romance with The Bangle and gladly became Starla’s boyfriend. But June was around the corner and I knew that I needed to be in Europe for the summer of 1985. I had rigged up a scam with Steve and Babs to keep each other in the transcontinental loop. We devised a way to call each other collect to payphones on specified times. They would be standing in a payphone on Rathmines Road and I’d be in a payphone on North Decatur Road and one of us would tell the international operator it was a collect call. We did this for months and the Irish and American phone companies never caught on. When Steve told me that U2 was playing in Dublin on June 29 with In Tua Nua and R.E.M., I had my summer agenda.

The fact that U2 was playing with R.E.M. made it like a summit of the new generation. Both were at the peak of their coolness. They were brand new sounds that had been around long enough to prove they weren’t one hit wonders, like Men Without Hats. Since R.E.M. was from Georgia and everyone is family in Georgia, I had plenty of back-stories about them, especially the patron saint of the hipster South, Peter Buck. One of those stories involved my flight to Dublin for this show.

The June 29th show was at Dublin’s Croke Park and since In Tua Nua was on the bill I got in again as a drum roadie. Arriving back in Ireland for my fourth summer abroad, I felt like a seasoned traveler. I had graduated from college and been accepted to graduate school in the fall. When I heard about the U2 show, I had only saved up enough to buy a one way ticket but I figured I had a few months to worry about how to get home. I’d be living the high life of a drum roadie now that In Tua Nua was on Island Records and my A&R work was being sponsored by Bono himself.

The show itself was wonderful. Pete Buck was surprised to see me backstage and I told him the whole Babs-Steve-Bono story. It was a sunny day and U2 had pulled a massive crowd. Squeeze was also on the bill. The Irish crowd had not yet caught on to the Southern gothic charm of R.E.M.. Their swirling music was an extension of the red clay in my blood but the lads and lasses just seemed confused. Fortunately, In Tua Nua, again at the bottom of the bill, dipped enough reels and jigs in their modern rock to keep the crowd warmed up for the Kings of Dublin. My all-access pass got me around all the security, but by this time U2 was, collectively, becoming as big as the John Paul 2, so I only briefly got to chat with Bono (who himself wasn’t the pope, yet). I got a friendly hug and up they went to the adoring adulation. Their encore included a version of Bruce Springsteen’s “My Hometown.” I felt in that moment how the kindred souls of artists crossed oceans and decades. I wanted in on that.

That summer I really began to feel like I belonged in Dublin. I knew my way around. I knew the locals. I knew music writers and music makers. I would go to birthday parties for B.P. Fallon, the famous Irish DJ. I’d go the home of Bill Graham, the famous Hot Press writer, and listen to Aretha Franklin records. Babs had even planned to fix me up with their new roommate, the very cool Clodagh Latimer. The problem was, I had quickly gotten over my ill-begotten romance with a Bangle and now had my first actual girlfriend. Although, my love of Starla didn’t stop me from spending a lot of time that summer with Clodagh’s friend, Sineád O’Conner, who was working delivering telegrams dressed as a French maid.

Being in Dublin with my double degree from Emory in my back pocket in Sociology and International Studies (turns out I was one credit shy of the Political Science major) made me relish my nights in the pubs even more. I fell in love with Irish pubs on my first visit. Here were halls full of people who were not watching prime TV, but having conversations. The political conversation was part of the DNA of the Irish. I learned more about U.S. policy in Latin America from a guy at the end of the bar at the Rathmines Inn than I did in all of my Ivy League courses and American “liberal” media. With a pint of the black water (Guinness to you), there were no strangers or off-limits topics. Way back in London, in 1982, I had learned to sublimate my Americaness. After all, Ronald Reagan was willing to make Europe the frontlines for his nuclear strategy. (When two tribes go to war, one point is all you can score.) But by 1985, my Irish accent seemed real.

There wasn’t as much roadie work as I had hoped so when In Tua Nua booked a show in London, I hitched a ride. I’d been planning on making it to London for the massive Live Aid show on July 13th and In Tua Nua’s show was on the 12th. Nowadays, I imagine most folks just fly, but in those days it was common practice to take the ferry and then train or coach it the rest of the way. I was becoming a veteran on that ferry. The band boarded together and we sang and played in the lounge as we made our way across the Irish Sea to Wales. Once we docked in Holyhead, the band hopped the speedy train to London and I was stuck in the more “scenic” coach.

The show was a big one for London as it was the coming out of The Communards, Jimmy Sommerville’s new group. I had been indoctrinated to his previous combo, The Bronksi Beat, earlier that year. I had moved around at the Turtles Record chain. After the Stone Mountain store, I moved to the Emory Village store, across from the university. Then I ended up at Ansley Mall Turtles. It was a great store, next to Piedmont Park and in the heart of Atlanta’s gay community. It was a big growing experience for a kid from a Klan town who was trying to leave his bigotries behind. And at the beginning of the summer of 1985, if a guy with a mustache and an undershirt walked in the store, there was a good chance he wanted a copy of Tina Turner’s Private Dancer or Bronski Beat’s Age of Consent. On cassette. I could see how the popularity of an out gay group meant so much to my gay workmates. Atlanta might have been an urban enclave but it was still in The South. So I was excited to see Sommerville’s new group.

Live shows in London are always about more than the music. It’s a scene. A global scene! Fans from all over the world are there, especially in the summer. In Tua Nua was on fire that night. Their new single, a cover of “Somebody to Love,” was getting airplay. I remember bassist Jack Dublin in rare form and Steve sailed away on the fiddle. After the show, a few jokes were made about the “gayness” of the audience but music fans were music fans and The Communards sounded amazing. I could feel the old homophobia melt away as Sommerville sang “You Are My World.” Love is the thing. Unfortunately, after packing up the gear we left the show early for a big dinner in London. I had one of those filet of sole dishes where the fish face stares right at you. But I knew I would need protein for the next day’s marathon.

I snuck out of the hotel early the next day to find my ticket for Live Aid. I had given a half-assed attempt to get one from Island Records, but I was never very good at that. It was too much like asking directions from your car. The Live Aid phenomenon was sweeping the globe and the concerts promised to be the definite music event of my generation and U2 was right in the middle of it!

It all began in late 1984 when Bob Geldof, of the Boomtown Rats, cornered Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher about butter. While famine gripped the people of Ethiopia, Britain sat on tons of surplus butter that could be used for cooking. One thing led to another and Geldof invented the celebrity all star single. “Do They Know It’s Christmas?” featured all the biggest British pop stars of 1984, including Adam and Bono from U2, billed as Band Aid. It was a moving moment in music, that’s been imitated a thousand times since. That Christmas, instead of gifts, I donated money to African famine relief in peoples’ names. I was hugely unpopular.

But the famine relief began to gain momentum. Michael Jackson and Quincy Jones did an American version of the Band Aid single called “We Are the World.” It was a cheesy mess, only rescued by the weird appearance of Bob Dylan. After that talk, began about the Live Aid concert. There would be two major ones, at Wembley Stadium in London and JFK Stadium in Philadelphia, with a host of smaller shows around the world, connected via satellite. I was only 5 years-old when Woodstock brought a generation together in 1969. I was 21 in 1985, and not going to miss this gathering of the tribes. The line-up was announced and was the who’s who. Most of the people who had been on the Band Aid and USA For Africa singles would be performing. Dylan would be in Philly, but Paul Weller, a major icon during my mod phase, would be playing with The Style Council in London. There were plenty of surprises as well. Led Zeppelin would reform for the US show and The Who would play Wembley. Paul McCartney was top of the bill for the UK show, so there was a massive rumor that there would be a sort of Beatles reunion, with Julian Lennon filling in for John. How the hell could I miss that?

With no real plan to get in, I hit Oxford Street and looked for touts selling tickets to the sold out event. Sometimes they hung outside record stores, like HMV, to scalp hot seats. It was too early and the streets seemed bare for a Saturday morning. I knew every music fan in London was on their way to Wembley. So I hopped a train north.

The train was full of musos talking about this phenomenal event. Queen would be there, and David Bowie. Somehow Prince Charles and Lady Diana were on their way. Phil Collins was supposed to play at both the London and the Philly shows. Were The Beatles performing? And of course, lots of excitement about the U2 set. I arrived at the platform and the word was out that the Bobbies were busting ticket scalpers right and left. This was a charity event, after all. A scared looking kid sold me a ticket for face value and then disappeared into the crowd. I was in! Miracles happen.

Inside the massive, sun soaked stadium I wasted no time in making my way right to the front. Since I was by myself, there was no reason to sit in the stands. I was going to see pretty much all my favorite performers in one day. I had to be as close as possible. I had gotten used to the crush of European shows and knew I would be getting intimate with a few thousand folks. With the flush of Royal Guard horns, the show began with Status Quo playing “Rockin’ All Over The World,” beamed in to TVs all over the planet. I instantly noticed the unity of the crowd. Heavy metal Quo fans bopping with trendy London kids who were there to see Nik Kershaw, along with the classic rock fans, all grooving to save the starving children of Africa. It was a unity that was sadly lacking when I went to the first Farm Aid concert later that year in Champaign, Illinois.

The summer heat was tempered for the crush of us in the front by hoses that sprayed down the crowd. This only created more heat as girls climbed on their boys’ shoulders to get the attention of the hosers. It was hard to focus on the films on famine in Ethiopia or the presence of Princess Diana with super-cool English girls being hosed down by men in front of the stage. When the live satellite link came in from the U.S. show things heated even more. It was The Beach Boys performing “California Girls” half a world away as the drenched London girls bobbed and danced. The world seemed united by rock music. I felt like I was part of something monumental, a global jukebox.

There wasn’t much down time between sets as the stage was sort of a rotating Lazy Susan and when one act would finish, the stage would just rotate 180 degrees and the next act would begin their short set. As Sade rotated away, the equipment for U2 rotated in. The crowd exploded. Yeah, a Beatle reunion would be godhead but, now that The Clash were gone, U2 was the only band that mattered. When Bono, Larry, Adam, and The Edge walked on stage you knew it would be one of those Woodstock moments, like Hendrix playing “The Star Spangled Banner,” that people would talk about forever. After all, U2 CARED. If there was any band of island guys that could save Africa, it was them. And they did not disappoint.

Each band got only 20 minutes to perform. It didn’t matter if you were Elton John or the Boomtown Rats. That meant that each act got about four or five songs. U2 played only two. They came on to the strident “Sunday, Bloody Sunday,” which seemed an odd choice in this moment of planetary unity. Were they trying set the Irish and English fans against each other? “I’m so sick of it!” I tried to get as close to the stage as possible. Maybe Bono would see me and pull me onstage to play another song. The crowd bounced to the marching beat of the hit.

But then they slid into “Bad,” the hypnotic song I had seen brought to life a year before in Windmill Lane. It was a perfect balance. The group had taken to extending the song live to work random songs into the simple structure. Today Bono carried them through the Stones’ “Sympathy for the Devil” and “Ruby Tuesday” and Lou Reed’s “Walk on the Wild Side” and “Satellite of Love,” which seemed perfect for the feed the world message that was being beamed around the Earth. Then something beautiful happened. U2 was playing to the 82,000 people in the stadium and the untold millions around the world (including every MTV viewer in the United States). But in the global audience, Bono brought it down to the most personal level.

He climbed down from the stage, apparently something organizer Bob Geldof had prohibited, and found one person. One girl. He hugged her while the band played the riff. He hugged her for a long time. It wasn’t a rock star hugging a fan. It was one person hugging another in a world full of pain and starvation. The whole thing took on a different feel at that moment as the embrace was projected on the massive jumbotrons and off to the satellites. People began hugging each other randomly. I looked up and saw Princess Diana wipe a tear from her eye. This wasn’t just about music. We were saving lives. Our own.

The rest of the day was an extension of the bliss. Dire Straits debuted their new song with Sting, “Money For Nothing,” which I would hear a million more times in 1985. Phil Collins did a set and then hopped on the Concord to make it to the Philly show to play with Led Zeppelin. When the supersonic jet flew right over Wembley, everyone in the stadium waved goodbye. Bryan Ferry was smooth and The Who were hard. David Bowie played my least favorite Bowie song (“Modern Love”) and my most favorite (“Heroes”), which brought another round of tears. Queen staged a massive comeback and had the entire place acting out the video for “Radio Ga Ga.” And then Paul McCartney appeared, complete with a broken P.A., to end the show with a version of “Let It Be.” It wasn’t a Beatle reunion, but it was a Beatle. My first. Everyone came in for the finale and then, in the middle of July, Bob Geldoff kicked off, “Do They Know It’s Christmas?” Feed the world.

The crowd continued to sing the chorus as the house lights came on. The stadium began to empty out and I realized I had been jumping up and down for 14 hours. No food, No bathroom break. Just pure musical bliss and I was as close to the magic as possible. There was a mad dash to the trains to get to any pub that had satellite TV (a rare thing in 1985). People had not had enough and wanted to see the rest of the U.S. show. I’d hope to catch it on RTE, the Irish network, as members of In Tua Nua, including Steve, were manning the phone banks and taking donations. I got to a pub in the West End in time to see Dylan, with Keith Richards and Ron Wood, play something. I couldn’t tell what. Some rambling thing that might have been a song. And then the far cheesier “We Are The World” finale, which didn’t really seem that cheesy any more. The talk of the pub was how much better U2 was than Bob Dylan himself, even if they were Irish.

I spent the next few days bumming around London. I put up about a hundred Nightporters stickers around town, especially outside cool clubs, like The Marquee. I took Sineád shopping on Carnaby Street and picked up some new mod clothes and caught a film. And I headed back to Dublin to spend the rest of the summer listening to fiddle players in pubs, tracking down rare Thin Lizzy and Christy Moore records and trying to not be American. Steve and I ran into Larry Mullen in Howth. He said he remembered my performance at the Atlanta show. Even if he didn’t, it didn’t matter. I was in the band.

When I finally came back to Atlanta, I had to find a new place to live. I lived in the dorms all four years of college and during the breaks I would stay on couches (usually Tim’s) or sneak into the dorm and camp in my room. Anything to stay out of Stone Mountain. So I was happy to land a very Parisian apartment in North High Ridge. It was an ancient apartment complex wedged between the punk rock neighborhood of Little 5 Points and the yuppie neighborhood of Virginia-Highlands. My first week there, I only had a sleeping bag, my stereo and a Jonathan Richman record. The third floor flat had branches from a massive oak tree that came into my porch overlooking North Avenue, so I dubbed the place The Treehouse. There were two murders on the block that week. I was right where I wanted to be.

As U2 became megastars, I heard less from Bono, but I still sent him tapes. The following spring he sent a short letter to the Treehouse to let me know the project was still on.

Randy,

Just a note from me… at the bottom of the sea…learning how to swim? Are you riding the crest of a wave – Are you still in love??

I see Steve and Babs and Mike Scott quite a bit now that I’m home. I still haven’t done a full appraisal of the USA tapes but so far so good. I will ring… and thanks again.

Bono

By 1986, Tim had left The Nightporters to form drivin’’n’cryin’, with Kevn Kinney. Tim had moved into the Treehouse and Kevn was sleeping on our couch. I sent Bono a tape of the band performing like on WREK, the Georgia Tech station. The news came around that U2 would be doing a big benefit tour for Amnesty International with a reformed Police. I had started the first Amnesty International chapter at Oxford College, so I was happy to see we were still on the same page, saving humanity.

Someone made a call somewhere and I found out that I was having lunch with Bono the day before the June 11 show at the Omni. It was actually Babs’ mom who arranged the thing. Mrs. Kernel was proud that her son-in-law was in show biz and invited Bono out to lunch, along with several U2 fans she knew. We met at a small bistro in midtown and when Bono arrived, he said hello to Mrs. Kernel and her flock and then made a B-line to me. He put his hand on my shoulder and said, “Randy, I am a drivin’’n’cryin fan.” I was quite pleased. First of all, he was actually listening to all this music I was sending him. But secondly, I thought Tim’s new band was something unique and really had potential. About a year later, drivin’’n’cryin’ was signed to Island Records, U2’s label, and I have to think that getting that cassette tape to Bono had something to do with it.

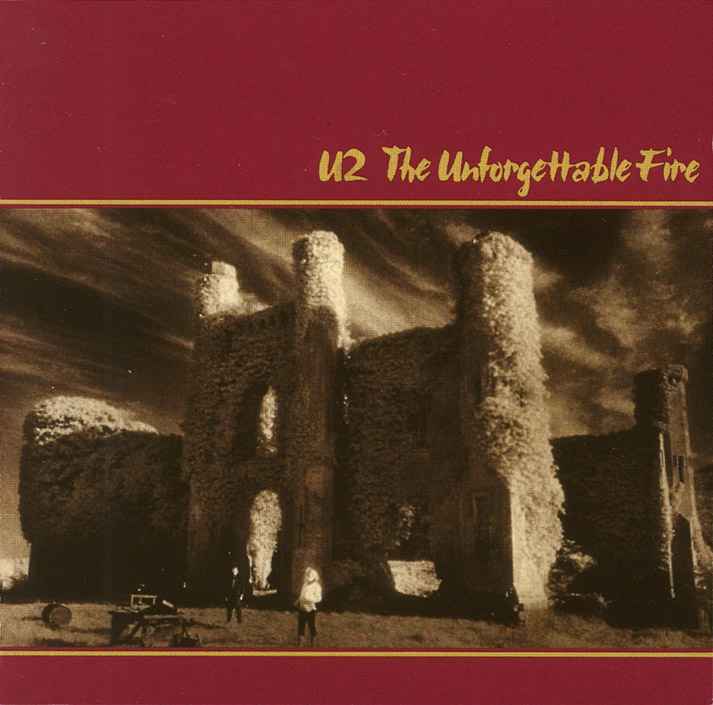

The lunch was fine. Bono ignored the guests for the most part as he and I talked politics and I munched my tuna melt. In the past year I had been getting deep into the Van Morrison back catalog. The previous summer in Dublin I had asked Steve Wickham what led him to move from playing classical violin to rock fiddle. Steve just slapped on Side 2 of Van’s 1979 album Into the Music, and it blew my fucking mind. And when I discovered Astral Weeks it was all over. I could see the direct link from “Madame George” to “Bad.” In a pause from the geo-political discourse, I looked at Bono and said, “You know, I understand where the magic of The Unforgettable Fire comes from. It’s Astral Weeks!”

He smiled and just said, “Shhhhh.” He then laid it all out. The magic of the Irish muse. “Randy, it’s like a river. It’s always there. You can just step into it. There’s a constant flow of creative energy. It’s available to all.” It was there in James Joyce’s Finnegan’s Wake. It was in the poetry of William Blake. And it was in the music of Van Morrison and U2. Could I tap into that? Wasn’t that how Jack Keroauc wrote? “First thought, best thought.” Maybe I should just start with a poem or two. That conversation had a huge impact on me. Yeah, I had zero musical talent, other than being able to stumble through “Knockin’ on Heaven’s Door” on an acoustic guitar. It gave me permission to step into my own river. It might be writing or it might be teaching. I would just let it go.

That afternoon we had a sociological conversation that I have been relating to my students ever since. We got into a deep discussion about the dysfunctional Irish family. Bono related how it all starts with the lack of birth control in Ireland. You can ban anything you want, but you can’t stop young people from having sex, which occasionally leads to pregnancy. Since Catholic nations frown upon “illegitimate” children, young couples get married at an early age. The young father is now stuck in matrimony. The older he gets, the more children that follow. Dad escapes to spend an increasing amount of time down at the pub with the guys. (For ages, Irish pubs were manly domains.) The absent father leaves a void back home that is filled by the eldest son. A close bond develops between the son and the mother, who misses the intimacy she had with the father. But when drunk dad comes home, there’s the classic male conflict over the protection and possession of the mother. It’s pure Freud.

Bono’s story became a staple for me for a couple of reasons. Ireland’s Catholic prohibitions created a black market for birth control (and no doubt back alley abortions). Each trip to Dublin I’d smuggle in a box of Trojans for my friends. Since they were a banned item, the rubbers would often end up tacked to a wall as a symbol of defiance. Fortunately for the women of Ireland, the island began allowing the sales of condoms in 1993 and legalized divorce in 1995. But the main reason I’d pull out Bono’s story is that it gives an example of why incest is a universal taboo, found in all cultures. Such conflicts can destroy the most important social unit there is, the family. Fathers and sons fighting over mothers or mothers and daughters fighting over fathers. Not good. Maybe Irish families are a little less functional than average. Maybe it’s a good thing that pubs close at 11 pm and not later. Regardless, when the topic of cultural taboos comes up, I can drop into the lecture, “I was having lunch with Bono one day…”

The Amnesty International show was great, of course. It was wonderful to see The Police back together again. And it was strange to see Joan Baez doing “Shout,” the Tears for Fears song. Peter Gabriel brought the house down with “Biko,” the song about the South African political prisoner. U2’s set ran through their more political a fare, all your MLK songs, “Sun City,” a Beatles song (“Help”) and two Dylan songs (“Maggie’s Farm” and “I Shall Be Released”). They were in full salvation mode.

My summers in Dublin in 1986 and 1987 I didn’t see Bono much. I was firmly in the Waterboys’ camp by then. Aside from running into Adam Clayton in the occasional pub, they were occupying the stratosphere. I had heard glimpses of their new album, The Joshua Tree, through Steven who was still the on-call fiddle player. It was clear that they were still in love with Americana and that this album would be a monster.

When it was released in the spring of 1987, I was in LA for one of my rock and roll holidays. My friend Kelly Mayfield had lent me her Nissan Sentra and I was cruising the city with KNAC blasting when they began debuting the new songs. I drove up to Mullholland Drive to the winding sound of “Where the Streets Have No Name.” It was bliss. The radio station had a special announcement – U2 tickets for a concert at the Forum would go on sale in 10 minutes. I saw several cars make U-Turns and head toward ticket outlets in Hollywood. I bombed down Lauralhurst Canyon Boulevard to “Bullet the Blue Sky.” By the time I got to Sunset, KNAC announced the show had sold out but a second would go on sale in a few minutes. More radical U-turns as kids heard the news along with the brilliant new songs. All over LA, the streets must’ve looked like a Seventies cop movie as U2 fans raced to ticket booths. I would be back in Atlanta on the date, so I just enjoyed the music with the windows rolled down in the Nissan. As I headed toward Beverly Hills, a third show went on sale. They were record sell-outs and every cool kid had to be there.

That summer I was back in Europe with a Eurail student pass. I needed to expand my radius of travel from my Dublin HQ. I explored Switzerland, Southern France, and Northern Italy, where my (now former) girlfriend, Starla, was living. I had three tapes in my Walkman; X’s See How We Are, Run DMC’s Raising Hell and The Joshua Tree. I was in Paris when The Joshua Tree tour stopped in the city of lights. I made a call and got two passes to the July 4th show at the Paris Hippodrome. A female friend of mine from Emory, Sharon, was going to school at the Sorbonne and I agreed to take her in exchange for a free place to sleep. The band was brilliant and I watched squeezed against the barricade. I got a bit angry at the French fans who tried to sing along to every song. This was my band! I lost my concert shirt in the crush and there was tear gas fired into the crowd, but the concert was eventually released on DVD and you can occasionally see my blonde head bobbing in the sea of bad French singers. The next morning I snuck out of the girls’ dorm at the Sorbonne (with the dorm master chasing me down the street and yelling rude things in his native tongue).

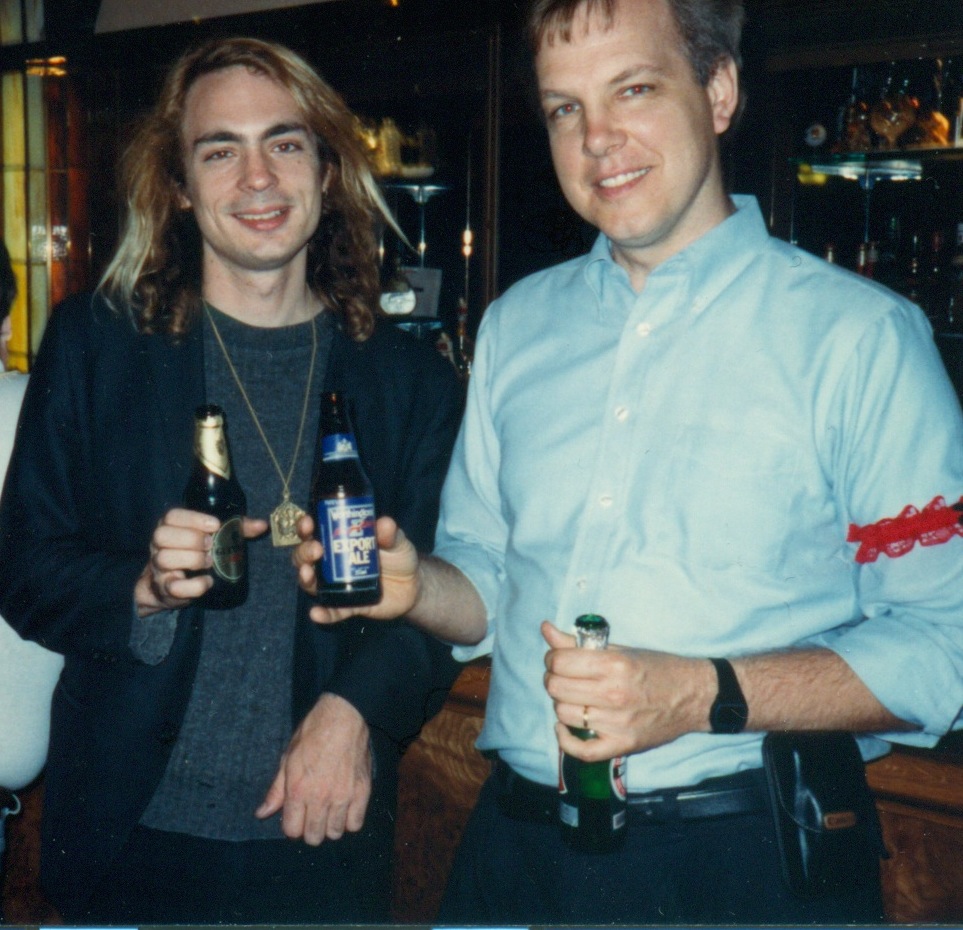

I had only been back in Atlanta a day when I got the call to head to New York to become drivin’n’cryin’s manager. Their deal with Island had them in RPM studio with Anton Fier producing. I had barely unpacked when I headed back to NYC to begin a month of big-time recording. I was sad that my big garage band project with Bono had fizzled, but if it had played any role in getting DNC on U2s label, that was enough. And now I was managing a band on Island Records.

U2’s tour finally hit the east coast while I was at the studio. On September 10, they were scheduled to play the Nassau Coliseum in Long Island. DNC’s A&R person, Kim Buie arranged three tickets for myself, Kim, and actor River Phoenix who had been hanging out with us in the studio. For some reason, on the night of the show, neither could go. River was nice enough to send his limo to haul me out to Uniondale. I was feeling blessed at being inside of U2 mania and gave the spare two tickets to guy who looked like a hard-up fan hoping for a miracle. Once inside the arena, I found those two seats occupied by a pair of college girls. They told me they had just bought them from some guy outside for a hundred bucks each. The dude owes me. With interest.

The band was now firmly in the zone. They were doing the shows that would become the Rattle and Hum film. Bono was older and more dramatic, lapsing into Morrisonesque spoken word bits about televangelists and El Salvador. He was morphing into a cult leader. Teenage boys were now dressing like him, with mullets and wide-brim hats. And girls would follow the Bono Boys around the arena hoping to touch the wannabe hem of their wannabe garments. I saw it many times. While I waited for River’s limo to rescue me from Long Island, I wondered where all this adoration would end up.

The tour finally made it to Atlanta on December 8, but I didn’t go. That’s the anniversary of John Lennon’s murder and it was the first annual drivin’n’cryin’ benefit for the homeless. Fortunately, U2 was doing two nights at the Omni, so I caught them on the ninth. My seats were on the floor, close to their little island stage that they would do a short set from. They opened with “Where the Streets Have No Name” and the crowd was rapt in ecstasy. When they came out to the little stage to sing “People Get Ready,” I caught Bono’s eye and got the nod.

We had breakfast at the hotel the next morning and, again, had trouble being seated because of our attire. But this time there was a copy of a recent Time Magazine in the lobby that just happened to have my breakfast date’s picture on the cover. Apologies all around. I slipped Bono a rough mix of the new DNC album and talked to him about how Starla had dumped me for some guy she met in Paris. (Why did I always feel the need to talk to him about my girl problems???) Mostly, we talked about the music and what it’s like to be at the center of a phenomenon. Bono paused for a moment and said, “I’m just a kid from the bad part of Dublin who wanted to be in a punk rock band.”

That was the last conversation I had with Bono. The popularity of drivin’’n’cryin’ didn’t keep pace with the supernova that was U2. Peter Buck told me he was asking for me backstage at the 1992 Zoo TV concert at the new Georgia Dome, but I no longer ranked high enough for a backstage pass. It seems like each show I was farther and farther away from the band. Just another fan. Bono had become a world actor for social justice. He got George W. Bush to significantly boost aid to African AIDS prevention. He kept his sunglasses on during his audience with the Pope. He’s the biggest rockstar on earth! And I’m just trying to rock my sociology classes. But I was at the Agora Ballroom in 1981. And yeah, that was me onstage, playing with the band.