June 29, 2017

To break things up, I’m occasionally posting chapters for the memoir I wrote a few years ago about my adventure with rock stars. Here’s one of two about U2. Chapter 1, about the Runaways is here: Queens of Noise

Chapter 2: U2 (Part 1 of 2) – I Will Follow

Soundtrack song: “Sunday Bloody Sunday”

The great thing about working at a record store was you got to get the new music first and listen to it for free. Before I got the job at Turtles, I would find out the release date of a new album and what time the store got its shipment and be there with bells on. In 1979, I was there to get new LPs by The Cars and George Harrison out of the box. First person in Stone Mountain, Georgia to hold a copy of Gary Numan’s Pleasure Principle in his hands. When I started at Turtles in 1981, this became a biweekly thrill; Tuesdays and Fridays. I had gotten the job thanks to David Riderick. David was the bass player for Riggs (who had two great songs on the Heavy Metal soundtrack in 1981) and worked at Turtles. When I was just a fan, he’d let me into the new shipments first. Finally he convinced Jimmy Cisson, the manager, to just hire this kid and let him open his own damn boxes. I’ll never forget opening the box for Michael Jackson’s Thriller in 1982 with a crowd of fans lined up at the door. I wasn’t the only one who needed the music ASAP.

Most of the world got U2’s first album, Boy, in late 1980. For obvious reasons (it was Stone Mountain), it didn’t show up at the Memorial Drive Turtles until early 1981. I was immediately interested because it was produced by Steve Lillywhite, who had recorded some XTC albums I was obsessed with (and my favorite Siouxsie & the Banshees song, “Hong Kong Garden”). It was exciting seeing how punk was evolving in the new decade. And I loved “breaking a new record;” selling an album or single to people who didn’t know they wanted it. Maybe that was a bit of my dad, the salesman, at work. A single by Diesel, “Sausalito Summernight” was a huge hit in America in 1981 largely because of my convincing people in Stone Mountain to buy it. Also, the success of The Go-Go’s. That was me.

I loved the ringing guitars and emphatic vocals of “Bono Vox” on Boy. The album just seemed important and I played it constantly in the store (and refused to play REO Speedwagon’s Hi Infidelity). Jeremy Graf, the lead guitarist from Riggs, was working part-time at the store during a big sale and hated the record. He’d tell me the band was “whiney” and would never go anywhere. Riggs was a great rock band and I’ll just leave it at that. Boy was a hard sell in Stone Mountain. We were selling tons of Kim Carnes records, but not much U2.

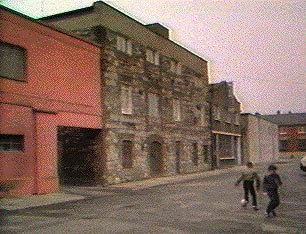

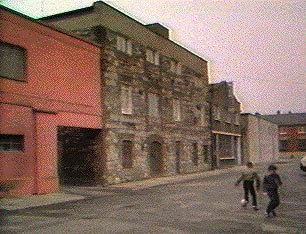

I could write a whole book about how the older Turtles, like Jeff Aronoff, Eric Wiggle, Nan Fischer, and David Remy, turned me on to real music. They would drag me to shows like B.B. King and say, “Randy, Eric Clapton is not the blues. THIS is the blues.” So I was thrilled when I saw that U2 was coming to the Agora Ballroom. The Agora was a small downtown venue across the street from the Fox Theatre that you had to be 18 to get in to. When I was in high school, I’d sit outside the stage door and listen to shows by The Pretenders, The Police, AC/DC, and The Clash (there is a picture from that show on the back of London Calling). My fake ID turned 18 on February 20, 1980 (my 16th birthday), and I became a regular at the Agora. The chance to bring my fellow Turtles to see my new favorite band would pay back all the great music they had turned me on to.

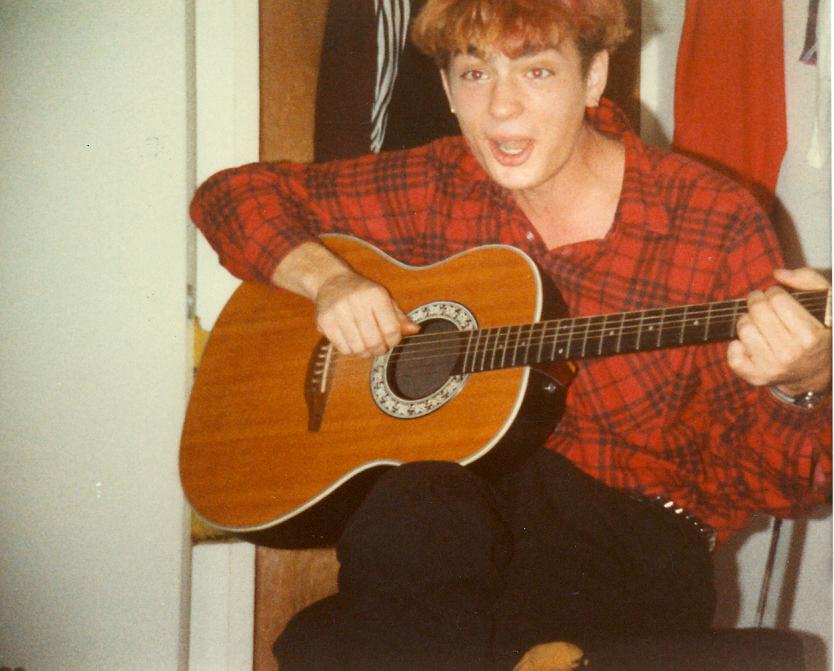

On May 6, 1981, The Agora was maybe half-full but U2 filled the place up with sound. Bono’s stage presence was hypnotic. On “I Will Follow,” he dramatically threw his cup of water into the air and it landed on Larry Mullen’s drums, bouncing off the skins. The band embodied the punk ideal of erasing the barrier between bands and fans. I knew that this would be another of my “I saw them when” moments. No doubt the 200 who were there still talk about that night in 1981. And one of the nice things was that at clubs like that, it was relatively easy to meet the performers. After the show, the band came back to the stage to break down the equipment. We talked to Bono about the show and how we were pushing Boy at the store. When my enthusiasm got the better of me, my workmates described me as the “baby Turtle.” I picked up a Penrod’s matchbook from the floor and asked him to sign it. He wrote, “To Randy, the baby Turtle, Bono.” I still have it inside my copy of Boy.

When their second album, October, came out, I got deep in to its mysticism. Was it a Christian album? I had wrestled with the wisdom of rejecting my Presbyterian roots, deep in the Bible Belt, for something more “spiritual.” I only knew that a rare airing of the “Gloria” video was the only reason to find MTV (which wasn’t available in much of the South yet). They opened up for the J. Geils Band and the Atlanta Civic Center on March 11, 1982. J. Geils had finally made it, thanks to their song, “Centerfold,” and U2 was still pretty unknown. Older rockers in the audience told me to sit down when U2 opened their set with “Gloria” and I leapt to my feet. By the last song, “Out of Control,” they had won over the crowd. After the concert, I tried to find my “friend,” Bono by the stage door but the opening band was long gone.

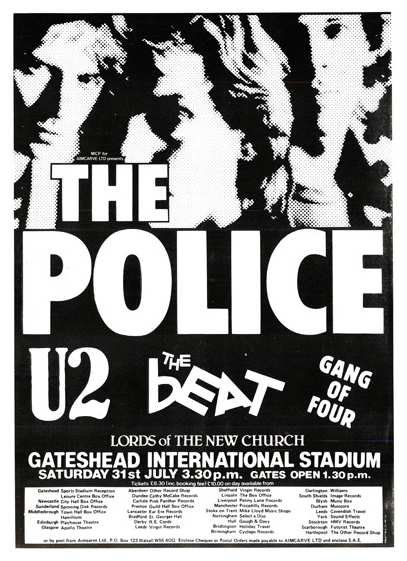

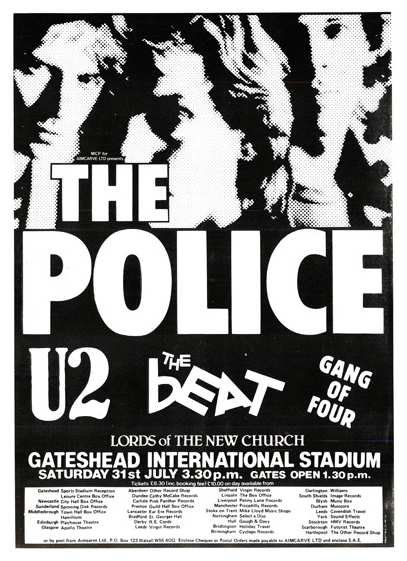

In the summer of 1982, I went off to school in London. I wanted to get away from Stone Mountain and get closer to the music I loved (especially all things Beatle-related). I had finished my freshman year at Oxford College and when the opportunity came to study in London, I caught the first flight from JFK to Heathrow. I saw a million shows that summer, from the massive to the tiny. I caught the Rolling Stones at Leeds, The Clash in Brixton, and The Lords of the New Church in a hotel bar in Hammersmith, where I had my arm pulled out of the socket while slam dancing. When I saw that U2 was opening for The Police up in Newcastle on July 31st, I went to a West End ticket office and a bought ticket for the show and the coach to ferry me up there. Seeing U2 playing to the huge arena of people who seemed to know every word was both super-cool and a bit sad. I knew I wouldn’t be watching them play at the tiny Agora again.

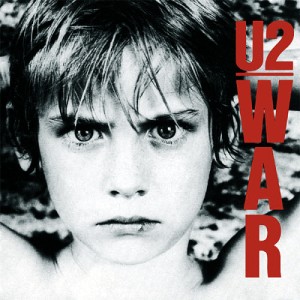

When I returned from London in the fall, I immediately began planning my return to the UK. If I had my summers off from college, there was no reason I couldn’t spend them in London, seeing bands and shopping for mod clothes on Carnaby Street. I’d work double shifts at Turtles and bank the money. Fortunately, I could use my employee discount on new albums, like U2’s third release, War. I really dug War because it was more political, like a Clash album. It captured the fear of living in Ronald Reagan’s Cold War, where the world could end at any minute. It only takes a second to say goodbye.

I was 19 and dating a women who was six years older than me with a young son. Reneé was a bartender at the 688 Club, the famous punk venue I was pretty much living in by 1983. Reneé’s best friend, Babs, was back from living in London for a bit and let me know her boyfriend, Steve, was the violinist on War. He added the chilling bit on “Sunday, Bloody Sunday,” among other accompaniment. When I mentioned to Babs that I was planning my return to London, she mentioned that she and Steve lived in a squat in Brixton (sight of the 1981 Brixton youth riots where I had gone to see The Clash play in the year before) and I was welcome to crash there. Perfect; a free crash pad in London with a guy that plays with U2.

After catching U2’s big headline show at the Atlanta Civic Center, with The Alarm opening, (I still couldn’t get backstage) I headed back to London. I caught the Victoria line Tube to the last stop, Brixton and walked down Electric Avenue to a massive abandoned apartment building. Squatters had taken over the flats on Cold Harbour Lane and if London had a ghetto, this was it. I stood in the rain and loved it, The Clash’s “Guns of Brixton” playing in my head. It was late and Babs looked a bit surprised when I knocked on the door, like, “Holy shit. This kid actually showed up!”

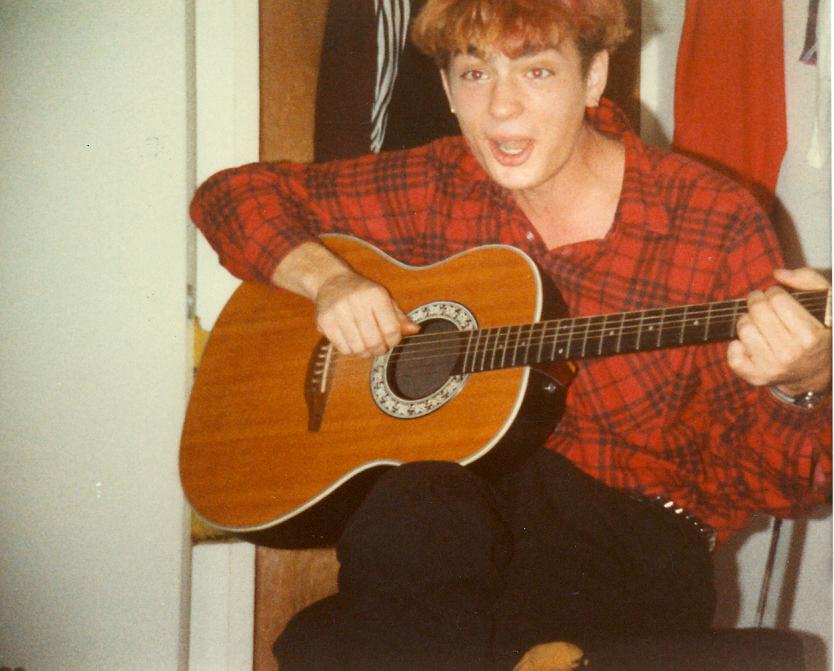

I instantly hit it off with Steve Wickham. He wasn’t just a name on a U2 record, he was a sweet funny Irish guy who loved American music. Since it was summer, the flat was never too cold and two more Irish roommates and a cast of visitors made my new home seem very warm, even if the hot water only came on once a week. I had taken to my punk lifestyle, dying my hair fuschia and getting tips from German punks who used egg whites to keep their spikes up. The French girls next door would occasionally dress me and I played Velvet Underground songs with the Irish buskers and, one night, told stories about hobbits during a party where everyone was on LSD but me.

Life on Brixton in 1983 was brilliant. There was a constant flow of reggae music bubbling up from windows and the market. There was a Marxist bookstore and an almost daily rally against South African apartheid. The squat was like a 24-7 scene from The Young Ones, with punks, mods, and Irish musicians showing up with cider and buckets of Kentucky Fried Chicken. I learned how to ride the Tube for free and would be yelled out by little old English ladies for blasting UB40 tapes out of my boombox in the subway.

The highlight of the summer was going to be a trip to Dublin. U2 was wrapping up their War tour with a big show in Phoenix Park on August 14 with Simple Minds, the Eurythmics, Big Country, and Steel Pulse. Steve left a week early to rehearse with the band. I took the coach to Holyhead, Wales with two Irish flatmates and their French girlfriends and then headed across the Irish Sea. It was the beginning of a long odyssey in Eire that would open my soul to the true power of music and revolution.

In Ireland, Steve had been reunited with his band, In Tua Nua. They were headquartered on the island of Howth, just to the east of Dublin. Drummer Paul Byrne had a cottage on the sea that was my crash pad for the week. The quaint place, on a high cliff above Balscadden Bay, also housed band member Vinnie Kilduff, who played the Irsh uillean pipes on War. In Tua Nua were about to be signed to U2’s new record label, Mother Records, with their new singer Leslie Dowdall (who had replaced one Sinéad O’Conner).

After getting settled, Steve and I hitchhiked up to the top of Howth, to The Summit pub. At the time, The Summit was really the only place to get a pint of the black water (aka Guinness) and some Irish bonhomie on the island of Howth. There we ran into Bono, who was relaxing in the days before the big homecoming concert. Steve was going to introduce me when Bono walked up and said, “Randy, the baby Turtle!” remembering our brief meeting in Atlanta two years earlier. This was my first glimpse into Bono’s sponge-like brain. We enjoyed a pint, talked about whatever country Reagan was overthrowing that week, and shared excitement about Saturday’s Phoenix Park show.

The concert was incredible. I spent some of it backstage (hanging out with The Alarm) but I was a big fan of every act on the bill. I was impressed at how European crowds sang along to every song and the Irish were twice as enthusiastic. The fans cooled the hot August afternoon by drinking from big mylar bags of cider that had been ripped from their cardboard boxes. Clouds of sweated-out cider and beer steam hung over the throng (I don’t think I ever went to a show in Europe were there were actually “seats”). When U2 hit the stage, the crowd was frenzied. It was like slam dancing with thousands of people. And when Steve and Vinnie joined the band, everyone cheered at two more of their hometown boys in the big league. I got to meet the rest of U2 after the show, Larry, Adam, and Edge, but it was all a blur. I was too excited to remember any of it.

I returned that fall to begin my junior year at Emory and have other musical adventures. I became the entertainment editor of The Emory Wheel and kept in touch with Steve and Babs and started saving for my trip back. After getting married, Babs and Steve left the squat in Brixton and moved to Dublin where Steve was going to devout his full time fiddling for In Tua Nua. It was agreed that I should plan on spending the summer of 1984 in Dublin and I could work as a roadie for the band.

June couldn’t come fast enough. Flying into Dublin from New York was much different than flying into London. The plane was filled with Irish souls heading home. There was much drinking and singing on the flight. Fiddles and whiskey were passed across the seats. It was a dose of the Irish muse that follows the Irish around, getting them through the hell of their history. Babs and Steve met me at the gate and we headed to their new flat on Rathmines Road.

The flat was small, but I had a little pallet in the back to sleep on. I figured I could earn my keep by telling tales of life in America, playing the latest cassettes, and, in general, being entertaining. There was also some big news that I knew about in advance. First, U2 was working on a new album at Windmill Lane Studios and Steve was going to lay down some violin parts. And second, my hero, Bob Dylan, was playing a massive outdoor concert on July 8 at Slane Castle. In Tua Nua was on the bill and I was going to be the drum roadie.

In the past year, I had become a student of Irish history and “the troubles.” When I was a student in London in 1982, the IRA had set off a series of bombs. One was under a bandstand in Regents Park where I often studied. I had a marginal bit of knowledge, mainly from two songs from 1972, John Lennon’s “Sunday, Bloody Sunday” and Paul McCartney’s “Give Ireland Back to the Irish.” I quickly added Eire to my radical history crash course after that, especially after my quick trip to Belfast in 1983, when British soldiers took the film out of my camera for taking pictures of the wrong thing (British soldiers). Slane Castle was on the River Boyne, near the site of the 1690 Battle of the Boyne. It was there that the Protestant King William defeated the Catholic King James, beginning a long history of foreign rule of Ireland. The concert would be a chance to experience the intersection of Irish and rock history.

I rode to the show in the van with In Tua Nua past the 100,000 people who wanted to be in the same physical space with the legendary Bob Dylan. The band teased me about wearing shorts and I informed them that this appropriate attire for a roadie at a festival. UB40 and Santana were on also on the bill. In Tua Nua, who had put out a wonderful 12 inch single on Mother Records, was now being courted by U2’s own label, Island Records. An A&R man from Island, known as The Captain, was waiting for us backstage. The Captain was a guy named Nick Stewart who had signed U2 to Island in 1980. But we were all more excited about being close to Dylan. He was a mythical character and none of us really knew what he looked like up close. I had seen him in 1980 at the Fox Theater, but I was about twenty rows back and the clouds of pot smoke and Frisbees were in the way. At one point, a guy that looked like the man walked by and a friend shouted out, “Welcome to Ireland, Mr. Dylan!” He turned around and with a smile said, “I’m not Bob but I’ll tell him you said so.” A guy that knew Bob Dylan, that was pretty close!

I was about to go bother Carlos Santana, who was standing alone on the banks of the Boyne when Paul Byrne asked me to come to the stage and help set up his drum kit. I was working after all. The crowd was the biggest I’d ever seen and when In Tua Nua started the set they roared in approval. Leslie looked great in her black leather skirt and very un-Irish tan. Steve lept about the stage wearing a polka-dot shirt I had found in the basement of Walter’s Fine Clothes in Atlanta. The band was tight and my big job was to make sure Paul’s vocal mike swung in when he had to sing background vocals. Being on stage with the band, hearing the music through the monitors, and looking down on the huge crowd was such a rush. If only I had a bit of musical talent that would justify me stepping out of the shadows.

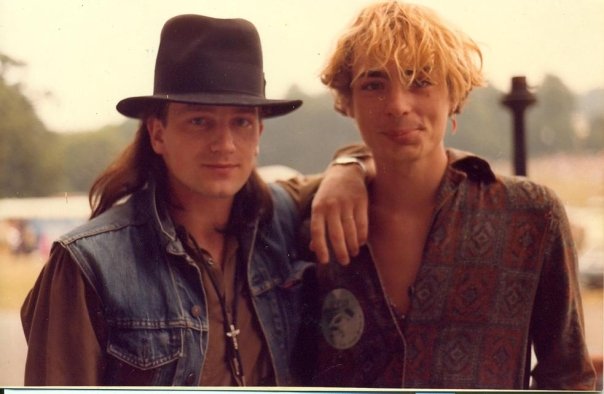

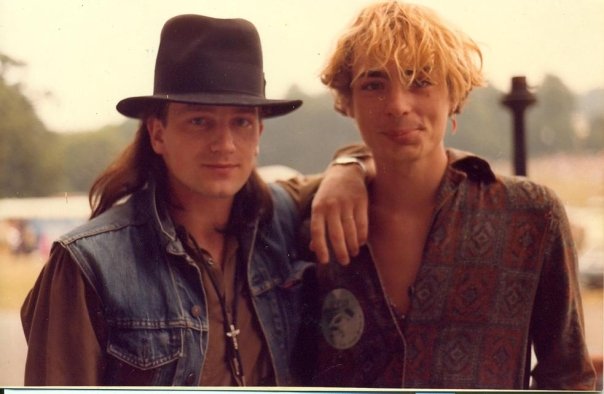

After their set, Steve and I headed up the castle to watch the UB40 set. U2 had been recording there with Brian Eno, so it wasn’t that surprising that we ran into Bono in the VIP area. He gave me a big hug and we talked about how great the In Tua Nua set was. Steve snapped a picture of us there and I have the goofiest look on my face. It was such a great day and about to get better. As much as I loved UB40 and Santana, I only remember hanging on Bono’s coattails, hoping he would introduce me to Eno. However, my All Access Pass meant that I could watch Dylan from a castle on a hill or from a few feet way.

I found a perfect spot in front of the stage, in front of the barrier that separated Bob from 100,000 screaming Dylan fans. I think the Irish cared more about Bob than the Americans did because, unlike TV obsessed Americans, the Irish actually care about poetry and politics. Bob was still in a bit of a lost phase (that he really wouldn’t emerge from until 1997), but when he opened with “Highway 61 Revisited,” you would have thought that he was the fucking messiah. I was ten feet from him the whole time, snapping pictures and hoping I wouldn’t run out of film before something major happened.

At the end of the show, Dylan announced a special guest and the patron saint of Irish music, Van Morrison walked on stage and the Boyne Valley erupted in jubilation. Bob and Van the Man dueted on “It’s All Over Now, Baby Blue” and “Tupelo Honey” and you could just feel the cosmic synergy. Then it was over. But the sweaty Irish masses demanded more. The summer sun was still up and there were a million more Dylan songs to get to. So out comes Bob and tells people there is another special guest, “Bono from U2!” But he pronounced “Bono” like “Bozo,” like “Bono the Clown.” The crowd loved it. It wasn’t just Bono out their with Dylan. Leslie and Steve were on stage too! And of course, I was out of film. Bob launched into “Leopard Skin Pill-Box Hat.” Bono and Leslie, not knowing the words (who does?) just sang “leopard skin pill-box hat” at odd moments and Steven fiddled away.

Bob played three more songs but I raced behind the stage to meet up with Leslie, Steve, and Bono, all who could not believe that they just performed with the actual guy that every busker in Ireland was trying to become. The sun was now down and I helped pack up the bands gear, wishing I had worn long pants.

After the show, we went to the Pink Elephant basement bar to celebrate the great gig. It was a classic 80s small disco bar with plenty of mirrors and colored lights. I would regularly see Def Leppard there. They were living in Ireland as a tax dodge and would huddle in a booth together with their pints of lager. Dublin in 1984 seemed like the least heavy metal place on earth. I got a kick out of telling them that my little brother (not me) was a big fan. They seemed to be happy that anyone knew who they were. I spent the rest of the night dancing to Frankie Goes to Hollywood songs with Sinead O’Conner. But that is another story for another chapter.

I think reuniting with Bono at Slane gave Steve permission to bring me down to Windmill Lane Studios, where U2 was working on their new album. We stopped in the Temple Bar first where we ran into Adam Clayton, the bass player. He was wearing a printed shirt with images of the Ku Klux Klan and burning crosses. I told him about growing up in a Klan town in Georgia and he talked about how the new album was going to be full of themes about American culture. Forget being the first to get the record out of the box, I was going to hear this album before it was even made!

In the studio, Bono was working on a song about the heroin problem in Dublin. He didn’t have any words for it but it would evolve into the epic, “Bad.” The band’s backing track played and Bono yelped and hummed and found words that fit the vibe. “Let it go!” The band was interested in Steve laying down some soulful lines on his fiddle and Bono gave him a demo tape to work with. I noticed a few cassettes in the trashcan and quietly slid them into my pocket. Bono seemed glad I was there and I later asked Steve if he could get me a job as a gofer in the studio so I could have a legitimate reason to hang out and watch the sessions. I got a call at Rathmines a few days later, while I was watching Miami Vice, to go pick up some bass strings for Adam. That was enough. And there is a song on Unforgettable Fire with a great bass part that are played on strings I bought.

Skimming the edge of the U2 inner circle was a thrill, but I had my own rock career to nurture. Since 1983, I had been helping out a great Atlanta band called The Nighporters that I will write more about. (They were the band that morphed into Drivin’ N’ Cryin’, the band that would dominate my rock n roll lifestyle for years to come.) By the summer of 1984, The Nightporters had a single, were selling out shows at 688, and had opened for The Clash. So I spent a good bit of time trying to break them in Ireland. I gave Bono a copy of a tape and I’d hunt down RTE DJs at the record station’s commissary and put the 45, “Mona Lisa,” in their hands along with a photocopy of a picture of the marquee at the Fox Theatre with The Nightporters’ name right below The Clash’s. To my credit, “Mona Lisa” blasted out across the Irish airwaves one night that summer.

My love of underground bands was the source of great interest for Bono. He knew there were scores of brilliant bands that would never have the success that U2 had. We talked about the Paisley Underground bands in LA, the hard-core bands in Washington, DC, and the drunken post-punk bands in Minneapolis. Bono hit on the idea of using Mother Records to get some of these groups more exposure and deputized me to collect demo tapes from unsigned bands that would expose the real sound of America. This was an easy task for me as there was a vast underground of music sharing that had nothing to do with computers. Bands would come through town, sleep on your couch and leave a handful of cassettes, like musical Johnny Appleseeds. I was actually looking forward to my return to the States to begin my job as Bono’s hipster A&R man.

The rest of the summer was filled with music and travel. I went to London with In Tua Nua to meet with The Captain at Island and watch the signing of the record deal. Nick and I had bonded after the Dylan show. We spent the next afternoon running up and down Grafton Street looking for a leopard skin pillbox hat for Leslie to commemorate her song with Dylan. At Island, there was a large white board with hand-written info about tours and releases from various Island acts. Standing in front of the wall was a big haired guy I recognized as Mike Scott of The Waterboys, another Island band.

I cut loose from the band to visit some students at my old London dorm. I made a trek down to Brighton in my parka, like a mod Hajj. A friend from college took pictures of me on the beach, trying to recreate the images from Quadrophenia. Then I headed off to Paris (in the days when you had to go across the English Channel, not under it). I ended up meeting some American girls from Colorado on the Champs Elysees and watched the L.A. Olympics in their hotel room while they smoked hash and asked me what it was like to be Irish. I put on my best Irish accent in the hopes it would charm them into letting me crash on the floor. Or in a bed.

One of the girls, Debbie, seemed to like all things Irish, including U2. I told her about life in Dublin and working with the band and told her she should visit some time. She was on a package trip and they were headed to London next. We made plans to meet in a few days. As I waited her outside her London hotel on Piccadilly Circus, a female copper tried to get me to move away, assuming I was trying to meet a prostitute. In Piccadilly Circus? Fortunately, Debbie came out in time and I gave her an Irish boy’s tour of London, careful not to drop my brogue I had been practicing all summer. I gave my address in Dublin (really Steve and Babs’ address) and sent her off on her package tour of Europe.

When I got back to Dublin, I decided it was time to head back up to the North. I took a train up to Belfast. I learned my lesson after my trip the previous summer and vowed to be more discrete around any soldiers. This time I was armed with books about the IRA, the loyalists, Green Republicans, and Orange coppers. On August 12, I took a train across the border into the North. This happened to be the same day that Martin Galvin was headed to Belfast. Galvin was an Irish-Lawyer who had been banned from entering Northern Ireland because of his leadership of NORAID. NORAID was an American group that provided supported financial aid to the IRA and Galvin was a major thorn in the side of the British government.

When I showed up in the Catholic neighborhood in Belfast where Galvin was going to speak with a bag full of books on Irish nationalism, I learned a quick lesson about global politics. I assumed that my American passport gave me international immunity from local conflicts. When the Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC) saw me snapping pictures of British soldiers (a serious transgression as the IRA targeted known soldiers), they questioned me, took my camera and my passport. They asked me if I was with NORAID. I tried to explain that my name was Czech, not Irish and, as much as I hated saying it, I was a tourist. That wasn’t good enough and I was held for questioning.

That might have been a good thing, since shortly after that, the RUC opened fire on the crowd that Galvin was speaking to. A guy about my age named Sean Downes was killed by a plastic bullet. The RUC questioned me on a side street. Once they realized I was a dumb American who had just listened to too many U2 records they let me go. They did wait until after the last train for Dublin had left and trailed me as I looked for a Bed & Breakfast to camp out in. The couple who ran it delighted me in tales of the “English savages.” When I made it back to college in the fall the whole experience became a part of my senior honors thesis, “A Marxist Analysis of the Irish Conflict.”

When I got back to Dublin from Belfast, there was a postcard from Debbie. She was coming to Dublin to see me. I went into a panic. I had pretended to be Irish because I thought being a kid from Stone Mountain, Georgia in Paris wouldn’t really get me anywhere. I explained my charade to Steve and Babs and they fell all over in hysterics. I begged them to help me keep up the act so I wouldn’t look like a complete idiot. When Debbie knocked on the door of the flat I quickly pulled her onto a bus for Grafton Street. Steve and Babs tagged along, constantly quizzing me on my Irish lineage and how Randy Blazak was actually a “very Irish name.” It was torture, We seemed to run into everybody the next few days. They all had the same puzzled look when I began to speak in my fake Irish accent. I’m not sure what Debbie made of it. Probably that I was an idiot.

That fall, back at college, I busied myself helping The Nightporters and finding tapes of cool bands for Bono. It was always cool when a letter from him would show up in my Emory PO box. When The Unforgettable Fire came out in October it just blew me away. It was such a departure from the strident War album. I would listen to the hypnotic “Bad” in my dorm room and think about the early version I heard Bono working on in Windmill Lane. And I knew the tour was going to be a major event.

During the spring, I was on top of my game. I had become the leading campus activist, leading demonstrations against apartheid and whatever Reagan was up to that week. I was flying to LA to hang out with rock star friends. I was loving my “Philosophy of Marxism” course, taught by a Catholic priest. The dogwoods were in bloom and my little clique of campus freaks had colonized the steps of Cox Hall. And on one sunny day, while I was organizing a protest, or a road trip, there was Debbie from Colorado. “Randy! What are you doing here?”