January 11, 2025

This series is intended to evaluate each product of the James Bond film franchise through a feminist lens, and the relevance of the Bond archetype to shifting ideas of masculinity in the 2020s.

Casino Royale (1967, directed by John Huston and others)

After four hugely successful Bond films, it’s time for the first Bond spoof. Casino Royale was the first of Ian Fleming’s Bond books (published in 1953). The John Huston directed film brings back many faces from the first four films from the the United Artists Bond canon, including Ursula Andress (who, as MI-6 agent Vesper Lynd, sounds way too much like Melania Trump). Casino Royale is a comedy meant to mock many of the Bond conventions, so it’s going to score differently than the films produced by Eon Productions, the home to “official” 007 movie franchise.

Here we get an older Bond, played by David Niven, who is 20 years retired after a sad end of a relationship with his beloved Mata Hari. He stutters and is known for his celibacy. This ain’t Sean Connery’s Bond. He’s brought back to MI-6 by M (played by Huston himself) to deal with evil SMERSH. (We don’t know what SMERSH stands for but there was a counter-intelligence group in the Soviet Union with the same name). M is comically killed so Bond takes the helm of MI-6, where he is reunited with Miss Moneypenny, or at least her daughter. (Strangely, Moneypenny now has an American accent, played by Barbara Bouchet, who was born in Nazi Germany.) He orders all the “Double O” agents to change their names to “James Bond” to confuse and trap SMERSH baccarat player Le Chiffre, played with gusto by Orson Welles. Two of those agents include Peter Sellers and a very young Woody Allen.

Casino Royale is a madcap farce that lampoons the cool image of 007. There’s even a yakety sax soundtrack during chase and fight scenes (some played by Herb Albert). The funny Bond quips are turned up to 11, jumping from wry to hilarious. (“James Bond doesn’t wear glasses.” Bond: “Yes, it’s just because I like to see who I’m shooting.”) The film is fully located in the mid-sixties. The first shot is graffiti that says, “Les Beatles.” The scene where the Peter Sellers’ Bond is drugged is straight psychedelia. And the movie introduces the Burt Bacharach song, “The Look of Love,” sung by Dusty Springfield (and sung by Bacharach himself in 1997’s Austin Powers: International Man of Mystery). The film was released in April 1967 and Sgt. Peppers Lonely Hearts Club Band was released shortly after setting up the iconic “Summer of Love.”

This may be an anti-Bond Bond film, piercing some of the tried and true tropes of the previous four films, but it’s worth dropping it into our feminist matrix if just for point of comparison.

Driver of Action – There are multiple drivers of the story here, including multiple Bonds. Sir James Bond (Niven) plays almost a support role. The majority of the story centers around Evelyn Tremble (Peter Sellers as a Bond surrogate) and Vesper Lynd (Andress). A section of the film follows Bond’s daughter with Mata Hari, Mata Bond (played by Joanna Pettet) in an adventure in Berlin (which features A Hard Day’s Night’s Anna Quayle and a hilarious scene where a hole is blown in the Berlin Wall and a wave of East Germans run out). This is an ensemble cast.

Role of Violence – It’s a Bond film so there a guns and explosions. But much of the violence is done for laughs, aided by a comedic soundtrack. But, other than an army of fembots with machine guns, there is no overt violence. I don’t think Niven’s or Seller’s Bonds kill anybody.

Vulnerability – The premise of this story is that Bond experienced heartbreak from his true love, Mata Hari, and looks for a connection to his daughter Mata Bond (who is abducted into a SMERSH flying saucer). He’s developed a stammer that he’s self-conscious of and his fighting style as become what might be describes as “effeminate.”

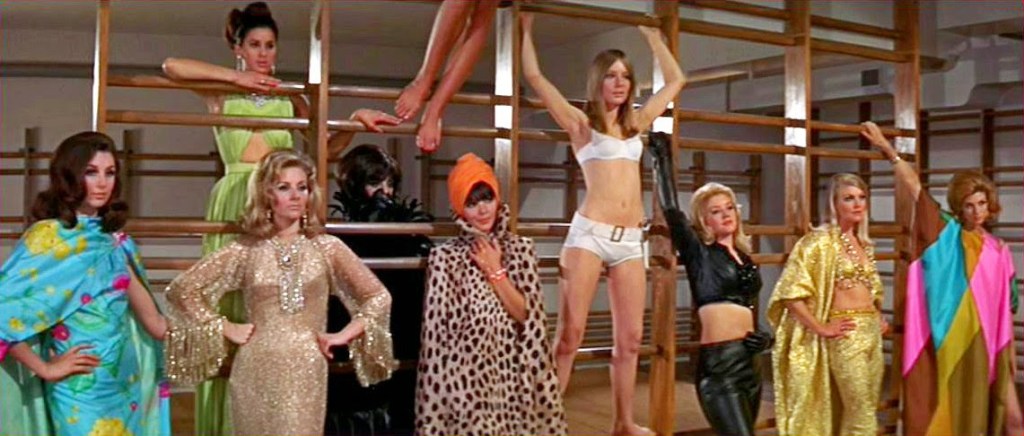

Sexual Potency – The joke of the movie is that Bond is celibate and that 00 agents are being killed because they can’t resist women. Bond creates a program to train agents to resist females in a scene where Agent Cooper rebuffs seductive women by throwing them to the mat. There is one scene where Sir Bond forcibly kisses Moneypenny (or her daughter). Ursula Andress plays seductress to Peter Sellers’ Bond, as does Miss Goodthighs (played by a young Jacqueline Bisset). Additionally, Dr. Noah (not Dr. No), played by Woody Allen, has a fourth quarter evil plot. He has a biological weapon that will make all women beautiful and kill all men over 4 foot 6, making him the tallest (and most sexually attractive?) man on earth.

Connection – There are few autonomous men in this film. The last quarter of the movie features Sir James, Moneypenny, Mata, and Agent Cooper working together to bring down Le Chiffre at the Casino Royale. And the Calvary (literally!) arrives to help save the day. Bond’s connection to his daughter seems sincere as is his desire to shepherd MI-6 in the post-M era. The film ends with the cast, having been blown up, floating in heaven, while Woody Allen’s character drops down to hell.

Toxic Masculinity Scale: 2

Summary Casino Royale is not a feminist critique of Bond. It’s a mid-sixties comedy so there are plenty of jokes rooted in sexism. For example, after M dies, Bond is sequestered in his house with his eleven seductive daughters (actually SMERSH agents) and his equally seductive widow (played with great hilarity by Deborah Kerr). But the film also completely mocks Bond’s Lothario reputation. (Woody Allen as James Bond should make the point.) There are plenty of nods to the Bond franchise, including an underground lair and even women in gold paint, but the ensemble nature of Casino Royale stands in stark contrast to Bond 1 to 4.

Unlike the previous film, Thunderball, whose cast is entirely gone, many cast members from Casino Royale are still with is, including Ursula Andress, Woody Allen, Joanna Pettet, Barbara Bouchet, and Jacqueline Bisset. I’d love to know how they see the film’s depiction of Bond and of women from a contemporary lens. The film is both hilarious and, at times, a complete mess, but also provided a break from the Bond formula. Sometimes stepping out of something allows us a fresh perspective on it. Two months later there would be another Sean Connery Bond flick headed to theaters. I wonder if viewers saw it differently after watching Casino Royale.

Next: You Only Live Twice (1967)

The James Bond Project #4: Thunderball (1965)

The James Bond Project #3: Goldfinger (1964)